George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

ORDER I. FEELINGS. GENUS I. PROPENSITIES.

The faculties falling under this genus do not form ideas, or procure knowledge ; their sole function is to produce a propensity of a specific kind. These faculties are common to man with the lower animals.

I. AMATIVENESS.

The cerebellum (FF, PL IV. and V.) is the organ of this propensity,1 and is situated between the mastoid processes

1 Partes génitales, give testes hominibus et fominis uterus, propensionem ad venerem excitare nequeunt. Nam in pueris veneris stimulus sominis secretion! sopè antecedit. Flures eunuchi, quanquam. testibus privati, hanc inclinationem conservant, Sunt etiam fominas qiise sine utero nate, Imnc stimnlum manifestant. Hinc quidam ex doctrin» nostr«

184 AMATIVENESS.

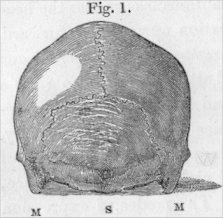

(M M, Fig. 1,) lying immediately behind and a little below 1- the

external opening of the ear on each side, and the projecting point or process

S, in the middle of the transverse ridge of the occipital bone. In the exit

on p. 116, No. 48 shews the situation of this process in a section of the

skull. The size of the cerebellum is indicated by the extension of the inferior

surface of the occipital bone backwards and downwards, or by the thickness

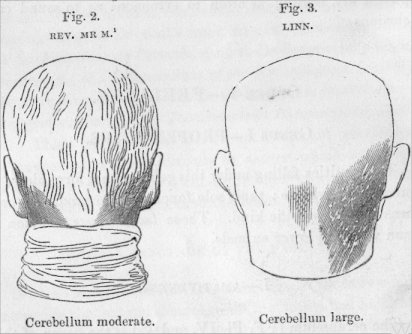

of the neck at these parts, between the ears. The difference between a moderate

and a large development, will be understood by observing the thickness of

the top of the neck in Figs. 2 and 3.

Cerebellum moderate. Cerebellum large.

inimicis, harum rerum minime inscii, seminis prsesentiam in sanguine con-tendunt, et hanc causam sufficientem existimant. Attamen argumenta hujus generis verâ physiologiâ longé absunt, et vix citatione digna viden-tur. Nonnulli etiam hujus inclinationis causam in liquore prostatico quserunt ; sed in senibus aliquando fluidi prostatici secretio, sine ullâ vene-ris inclinatione, copiosissima est. Spurzheim's Phrenology, p. 128. -

* Trans, of the Phren. Soc. p. 320. * Phren. Journ. vol. x. p. 207.

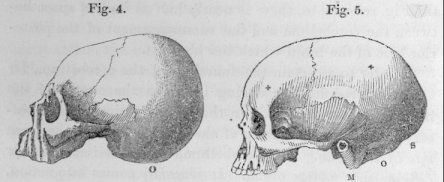

In some individuals, the lobes of the cerebellum descend or droop, increasing the convexity of the occipital bone, rather than its expansion between the ears. In Fig. 4, O represents a large development downwards, of that part of the base of the occipital bone commonly called the posterior occipital swelling or fossa. In such cases, the projection may be felt during life by the hand, if firmly pressed on

the neck.

In the skull Fig. 5, the distance between M, the mastoid process, and S, the spine of the transverse ridge of the occipital bone, is large, although the occipital swellings, O, do not droop as in the preceding skull. In both Figs. 4. and 5. the cerebellum is large, but smaller in 5. In the former, however, the large size is indicated by the drooping of the bone ; in the latter, by the large circumference backwards from ear to ear, or by a thick neck. The external muscles of the neck are attached to the skull in the line of this circumference.

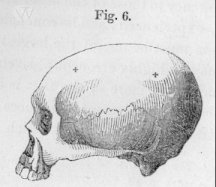

In this skull (Fig. 6.), the cerebellum is small,

and it will be seen that the base of the Fi 6 occipital

bone extends only a short distance backwards from the mastoid process, while

the occipital swelling does not descend as in

Fig. 4.

Within the skull, and on the same plane with the

186 AMATIVENESS.

occipital process, lies the tentarium, a strong membrane, which is co-extensive with the upper surface of the cerebellum, and separates it from the brain. It is inserted into the inner surface of the occipital bone at 48 in the Fig. on p. 116. In some animals which leap, this separation is produced by a thin plate of bone ; but Dr "Vimont says that this rule is not universal, as the tentorium is membranous in the squirrel, hare, and in some other animals which leap. At 48 in the Fig. referred to, there is nearly half an inch of space between the cerebellum and the commencement of the posterior lobe of the brain which lies above it.

In order to ascertain the functions of the cerebellum, Dr Gall compared its size during life with the energy of the instinct of reproduction. In this investigation, it is necessary to consider the nature of the propensity, and the great size of its organ. The cerebellum, even when moderately developed, is a large organ. It generally comes into action, not, like the others, gradually, and in the course of a series of years, but rapidly and with great vigour at the arrival of puberty. Persons unacquainted with these facts are liable to err in their estimate of the proportion which should exist between the strength of the propensity and the size of the organ. They expect to find a large cerebellum, when a practised phrenologist would look for one of only moderate dimensions- To remove this source of error, I observe that, from the cerebellum being a large organ, and from its coming rapidly into play, the impulses which it communicates are often felt by the individual to be superior in intensity and urgency to those of the other feelings which he had previously experienced ; and he concludes that, therefore, his cerebellum must be one of the largest possible dimensions which may be highly erroneous. Even a moderate-sized cerebellum, and much more so one that is of full size, combined with an active temperament,1 produces feelings of very considerable strength. The objects which excite the instinct (beings of

1 The influence of the temperaments has already been oxphiined in this work. p. 40.

the opposite sex) are frequently presented to the mind, invested with all the attractive influences of youth, grace, beauty, often heightened too by the highest mental accomplishments, and the most exquisite refinement ; and considering the size of the cerebellum, even when moderate, in relation to that of the largest organs of the sentiments, Benevolence, for instance, or Veneration, we need not be surprised that the feeling of sexual love should, even in such cases, be powerfully experienced.

When the cerebellum is really large, and the temperament active, the individual becomes distinguished from his fellows by the predominance of his amorous propensities. In all his vacant moments, his mind dwells on objects related to this faculty, and the gratification of it is the most important object of his thoughts. If his moral and intellectual organs be weak, he will, without scruple, invade the sanctity of unsuspecting innocence and connubial bliss, and become a deceiver, destroyer, and sensual fiend of the most hideous description.

These observations will enable the reader to understand what degrees of intensity in the instinct may be expected to accompany different degrees of development of the organ.

The cerebellum is connected with the brain ; for its fibres originate in the corpora restiformia, from which also the organs of other animal propensities arise. Certain fibres originating in that source, after passing through the optic thalami, expand into the organs of Philoprogenitiveness, Adhesiveness. Combativeness, Destructiveness, &c. The nerves of sight (2, 2, pi. iv.) can be traced into the nates, lying very near the same parts ; while the nerves of hearing (8, same plate), spring from the medullary streaks on the surface of the fourth ventricle, lying immediately under the cerebellum. These arrangements of cerebral and nervous structure correspond with the facts, that the eyes express most powerfully the passion of love ; that abuses of the amative propensity produce blindness and deafness ; and that this feeling subsequently excites Adhesiveness, Combative-

188 AMATIVENESS.

ness, and Destructiveness, into vivid action rendering attachment irresistibly strong, and inspiring even females, who, in ordinary circumstances, are timid and retiring, with courage and determination when under its influence.

The cerebellum consists of three portions, a central and two lateral. The central is in direct communication with the corpora restiformia, and the two lateral portions are brought into communication with each other by the pans Varolii. (See fig. 5, p. 116 ; and plate iv.)

Dr Gall was led to the discovery of the function of this organ in the following manner. He was physician to a widow of irreproachable character, who was seized with nervous affections, to which succeeded severe nymphomania. In the violence of a paroxysm, he supported her head, and was struck with the great size and heat of the neck. She stated, that heat and tension of these parts always preceded a paroxysm. He followed out, by numerous observations, the idea, suggested by this occurrence, of connexion between the amative propensity and the cerebellum, and he soon established the point to his own satisfaction.

This faculty gives rise to the sexual feeling. In newly born children, the cerebellum is the least developed of all the cerebral parts. At this period, the upper and posterior part of the neck, corresponding to the cerebellum, appears attached almost to the middle of the base of the skull. The weight of the cerebellum is then to that of the brain as one to thirteen, fifteen, or twenty. In adults, it is as one to six, seven, or eight. The cerebellum enlarges much at puberty, and attains its full size between the ages of eighteen and twenty-six. The neck then appears greatly more expanded behind. In general, the cerebellum is less in females than in males. In old age it frequently diminishes. There is no constant proportion between the brain and it in all individuals ; just as there is no invariable proportion between this feeling and the other powers of the mind. Sometimes the cerebellum is largely developed before the age of puberty. This was the case in a child of three years of age, in a

AMATIVENESS. 189

boy of five, and in one of twelve ; and they all manifested the feeling strongly. In the cast of the skull of Dr Hette, sold in the shops, the development is small, and the feeling corresponded.1 In the cast of the skull of J. L., a convict who died at Chatham, it is very large, and there was a proportionate vigour of the propensity.2 In the casts of Mitchell and Dean, it is very large, and the manifestations were in proportion. Farther evidence of the functions of this organ will be found in Dr Gall's work Sur les Fonctions du Cerveau, tome iii. pp. 225-414 ; and other cases are mentioned in the following works : Journal of Pathological Observations kept at the Hospital of the Ecole de Médecine, No. 108, 15M July 1817, case of Jean Michel Brigand ; Journal of the Hôtel Dieu, case of Florat, 19th March 1819, and of a woman, 11th November 1818 ; Wepferus, Historia Apoplecticorum, edit. 1724, page 487 ; Philosophical Transactions, No. 228. case by Dr Tyson ; Mémoires de Chirurgie Militaire, et Campagnes, by Baron Larrey, vol. ii. p. 150, and vol. iii. p. 262 ; Serres On Apoplexy ; Richerand's Elements of Physiology, pp. 379, 380, Kerrison's translation ; Dr Spurzheim's Phrenology, p. 130 ; The Phrenological Journal, vol. v. p. 98, 311, 636 ; vu. 29 ; viii. 377, 529 ; ix. 188, 383, 525 ; xi. 78 ; xiv. 380, 240 ; xv. 340 ; Dr Andrew Combe's Observations on Mental Dérangement, p. 161 ; The London Medical and Surgical Journal, 21st June and 23d August 1834, vol. v. p. 649, and vol. vi. p. 125 ; The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, July 1839, p. 283, and April 1840, p. 519 ; and The Dublin Journal of Medical Sciences, September 1840, p. 151. Dr Caldwell has given, in The Annals of Phrenology, vol. i. p. 80-84, a summary of the principal reasons for considering the cerebellum to be the organ of Amativeness.

" It is impossible," says Dr Spurzheim, " to unite a greater number of proofs in demonstration of any natural truth, than may be presented to determine the function of the cerebellum ;" and in this I agree with him. Those who have not

1 See Phren. Journ. vi. 600. 2 Id. iv. 258.

190 AMAT1VENESS.

read Dr Gall's section on this organ, can form no adequate conception of the force of the evidence which he has collected.1 M. Flourens, by whom certain experiments were performed on the lower animals, chiefly "by inflicting injuries on their cerebella, contends that these experiments shew that the cerebellum serves for the regulation of muscular motion. " On removing the cerebellum," says he, " the animal loses the power of executing combined movements.5' Magendie performed similar experiments on the cerebellum, and found that they occasioned only an irresistible tendency in the animal to run, walk, or swim backwards. He made experiments also on the corpora siriata and tubercula quadrigemina, with the following results : when one part of these was cut, the animal rolled ; when another, it went forward., and extended its head and extremities : when another, it bent all these : so that, according to this mode of determining the cerebral functions, these parts of the brain possess an equal claim with the cerebellum to be regarded as the regulators of motion. The fact is, that all parts of the nervous system are so intimately connected, that the infliction of injury on one deranges others ; and hence this is not the way to determine the functions of any, even its least important parts. This is now admitted by all sound physiologists ; among others by Sir Charles Bell.2 Mr Solly (p. 57.) has described certain fibres which arise from the summit of the anterior or

1 The nature of the subject prevents me from inserting the details of Dr Gall's section on this organ. I have translated it, however, and printed it uniformly with this work (On the Functions of the Cerebellum : Maclachlan and Co., Edinburgh ; Longman, and Co., London ; 1838); and it may be obtained separately by medical students and others who wish to pursue the investigation. In the same volume I have translated the observations of Dr Vimont and Dr F. J. V. Broussais on the organ and propensity of Amativeness, and added a number of illustrative cases collected by myself, some of which are referred to in the text. With respect to the functions of the cerebellum, the reader may consult also The Lancet of 28th April and 15th September 1838 ; The Medico-Chirurgical Review, October 1838, p. 567 ; October 1840, pp. 533 and 562 ; April 1842, p. 280 ; and The Phrenological Journal, xiv. 94, 287-8 ; xv. 269, 378.

' See The Phrenological Journal, ix. 122.

AMAT1VENESS. 191

motory column of the spinal marrow, and from the lower extremity of the corpora pyramidalia, also the motory tract, and proceed upwards and laterally, and enter the cerebellum. In cutting deeply into the cerebellum, these fibres would be irritated, and through them irritation would be communicated to the whole of the motory tract of the spinal marrow. It is not difficult, therefore, to account for the disturbance of motion which ensued from the experiments of Flourens and Magendie. Dr Gall has ably commented on these experiments, and shewn that they do not infringe on the functions assigned by him to the cerebellum.1

The great size of the cerebellum, however, the circumstance of its lateral portions not bearing the same relation to the middle part in all animals,2- and also the results of some late experiments, have suggested the notion that it may not be a single organ, but that, although Amativeness is unquestionably connected with the largest portion of it, other functions may be connected with the other parts. This seems not improbable ; and in the appendix, No. IV, I have stated the results of the most recent experiments and observations in support of this proposition.3

In Magendie's Journal de Physiologie, for June 1831, a case is reported, in which the cerebellum was found on dissection to be wanting, having apparently been destroyed by disease. Yet the patient enjoyed to the last the power of executing combined movements, and performed none of the evolutions described above as the result of Magendie's experiments.4

1 See translation of Gall on the Cerebellum, p. 95.

* As to the cerebellum in the lower animals, see The Phrenological Journal, xiv. 185 7-

' See The Phrenological Journal, vii. 440.

4 The case alluded to, that of a girl named Labrosse, who was addicted to amative abuse, is reported likewise in Ferussac's Bulletin for October 1831, and has been proclaimed by the enemies <tf Phrenology to be utterly subversive of the science. Dr Caldwell, however, has well shewn, in the Annals of Phrenology, vol. i. p. 7G (quoted in The Phrenological Journal. vol. ix. p. 226, and in my compilation On the Functions of the Cerebellum.

192 AMATIVENESS.

Mr Scott, in an excellent essay on the influence of this propensity on the higher sentiments and intellect,1 observes, that it has been regarded by some individuals as almost synonymous with pollution, and the notion has been entertained that it cannot be even approached without defilement. This mistake has arisen from attention being directed too exclusively to the abuses of the propensity. Like every thing that forms part of the system of nature, it bears the stamp of wisdom and excellence in itself, although liable to abuse. It exerts a quiet but effectual influence in the general intercourse between the sexes, giving rise in each to a sort of kindly interest in all that concerns the other. This disposition to mutual kindness between the sexes does not arise from Benevolence or Adhesiveness, or any other sentiment or propensity, alone ; because, if such were its exclusive sources, it would be equally displayed in the intercourse of the individuals of each sex among themselves, which it is not. " In this quiet and unobtrusive state of the feeling," says Mr Scott, " there is nothing in the least gross or offensive to the most sensitive delicacy. So far the contrary, that the want of some feeling of this sort is regarded, wherever it appears, as a very palpable defect, and a most unamiable trait in the character. It softens all the proud, irascible, and antisocial principles of our nature, in every thing which regards that sex which is the object of it ; and it increases the activity and force of all the kindly and benevolent affections. This explains many facts which appear in the mutual regards of the sexes towards each other. Men are, generally speaking, more generous and kind, more benevolent and charitable, towards women, than they are to men, or than women are to

above mentioned, p. 171), that such a conclusion is altogether unwarranted. -Although the cerebellum was found, on dissection, to be almost obliterated, the appearances were such as plainly to indicate that the obliteration was recent, and had been caused by inflammatory excitement of the organ an excitement perfectly in harmony with the manifestations referred to.

1 Phrenological Journal, ii, 392. 5

PHILOPROGENITIVENESS. 193

one another." This faculty also inspires the poet and dramatist in compositions on the passion of love ; and it exerts a very powerful influence over human conduct. Dr Spurzheim observes, that individuals in whom the organ is very large, ought not to be dedicated to the profession of religion, in countries where chastity for life is required of the clergy.

The organ is more prone to activity in warm than in cold climates. When very large, however, its function is powerfully manifested even in the frozen regions. The Greenlanders and other tribes of Esquimaux, for example, are remarkable for the strength of the feeling ; and their skulls, of which the Phrenological Society possesses twenty-one specimens, indicate a large development of the cerebellum.1

The' abuses of this propensity are the sources of innumerable evils in life ; and, as the organ and feeling exist, and produce an influence on the character, independently of external communication, Dr Spurzheim suggests the propriety of instructing young persons in the consequences of its improper indulgence, as preferable to keeping them in "a state of ignorance that may provoke a fatal curiosity, compromising in the end their own and their descendants' bodily and mental constitution."

The organ is regarded as established.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.