George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

APPENDIX. 425

No. II

Text, page 181.

Objections to Dr Spurzheim's Classification of the Mental Faculties. By- Robert Cox. Abridged from the Phrenological Journal, vol. x. p. 154.

Every mental faculty is capable of acting in various forms ; in other words, it may exist in different states, each giving rise to a distinct variety of consciousness-a distinct affection of the mind.1 The sense of feeling, for example, is one of the fundamental faculties, but the consciousness resulting from its activity is modified according to the particular state in which its organs happen to be, from the influence of some external or internal cause. Thus, when we hold our fingers near the fire, the sensation of heat arises, and this is one affection or mode of action of the faculty. If we prick the skin with a needle, the affection is that of pain : tickle the soles of the feet, and the sensation of itching follows : dip the hands into melting snow, and the sensation of cold is experienced. All these affections, it will be ob-.served, are referrible to one faculty alone ; they are modes of action of a single power.

The affections or modes of action of the fundamental powers are divided by Dr Spurzheim into qualitive and quantitive affections ; that is to say, first, those which differ in kind, as the sensation of heat differs from the sensations of pain, cold, and itching ; and, secondly, those which differ in intensity or power. The sense of taste, for example, is, like that of feeling, subject to modifications, giving rise to different affections or states of consciousness. According to the nature of the substances taken into the mouth, the affection is that of sweetness, bitterness, sourness, acritude, and so on. These are qualitive affections of a single faculty-affections different in kind, and not merely in

1 I employ the word affection as it is used by Dr Spurzheim, " solely according to its etymology, to indicate the different states of being affected of the fundamental powers." See his Philosophical Principles of Phrenology, p. 43. In this section the last (American) editions of Dr Spurzheim's works are quoted.

426 APPENDIX.

degree. The sense of smell, in like manner, is modified when stimulated by different odoriferous substances ; and that of hearing is variously affected by different sounds, as shrill, grave, creaking, and whistling. So also the sentiments of pride and contempt are two qualitive affections of the single faculty of Self-Esteem.

The quantitive affections are no other than the qualitive existing at different points in the scale of intensity, quantity, or power ; a single qualitive affection often receiving different names, according to its degree of force. Thus, one general qualitive affection receives at various points in the scale of intensity the names of velleity, desire, longing, and passion ; one general qualitive affection of Acquisitiveness or Love of Approbation is called at a certain point pleasure, at another joy, and at a third ecstasy ; while another general qualitive affection of the same faculties is termed on one occasion pain, on another grief, and on a third wretchedness or misery. The special qualitive affection of Cautiousness called fear includes the quantitive affections of wariness, apprehension, anxiety, terror, and panic.

It happens with many of the faculties that their affections are of two kinds : lst, an inclination or propensity to act in a particular way ; and, 2dly, certain emotions or sentiments which accompany, but are easily distinguishable from, propensity. Thus, one affection of Acquisitiveness is an inclination to take possession of property and to hoard it up, while another is the sentiment of greed. Self-Esteem is the source of an inclination to wield authority, and at the same time of the emotion which its name denotes, including the various quantitive affections of self-satisfaction, self-reliance, self-importance, pride, and overweening arrogance. Contempt, which is a qualitive affection of the same faculty, falls, like the emotion named self-esteem, within the second or sentimental class of affections. Upon the existence of these two kinds of affections Dr Spurzheim has founded an important part of his classification.

Gall and Spurzheim agree in dividing the mental faculties into two great orders ; the first comprehending what are termed the dispositions, and the second the powers of the understanding. This division has been recognised from the remotest antiquity, under the names of soul and spirit (l'âme et l'esprit}, will and understanding, the moral and intellectual faculties, heart and head. Dr

APPENDIX. 427

Spurzheim calls the former the feelings or affective faculties,'1 of which, says he, " the essential nature is to feel emotions ;"2 and the latter the intellectual faculties, whose " essential nature is to procure knowledge."3 To the designation intellectual faculties it appears impossible to object ; but as it is by no means evident that emotions are peculiar to the faculties called affective, the use of that term, as denned by Dr Spurzheim, seems to be improper. In fact, many general emotions are modes of action of the intellectual as well as of the affective powers. Every faculty, without exception, desires ; and what is desire but an emotion ? Every faculty experiences pleasure and pain, and are not these emotions ? Take the sense of taste as an example. This, being an intellectual faculty, experiences, according to Dr Spurzheim, no emotion ; but, as Dr Hoppe of Copenhagen has already inquired, " when we sit down, delighting in the dainties of a well-stored table, is not then the working of the sense wholly affective ?"* I propose, therefore, to define the affective faculties as those of which the essential nature is to feel emotions, or inclinations, or both., but which do not procure knowledge.

Dr Spurzheim's classification, however, does not stop here. " Both orders of the cerebral functions," says he, " may be subdivided into several genera, and each genus into several species. Some affective powers produce only desires, inclinations, or instincts ; I denominate them by the general title propensities. The name propensities, "then, is only applied to indicate internal impulses which invite to certain actions. They correspond with the instincts or instinctive powers of animals. There are other affective faculties," he continues, " which are not confined to inclination alone, but have something superadded that may be styled sentiment. Self-Esteem, for instance, produces a certain propensity to act ; but, at the same time, feels another emotion or affection which is -not merely propensity."5 The affective faculties named by Dr Spurzheim propensities, are Amativeness, Philoprogenitiveness, Inhabitiveness, Adhesiveness, Combativeness, Destructiveness, Secretiveness, Acquisitiveness, and Constructiveness ; those which he calls sentiments are Self-Esteem, Love of Approbation, Cautiousness, Benevolence, Veneration, Firmness, Conscientiousness,

1 Phenology, p. 131. 2 Phil. Prin. of Phren.,

p.48.

3 Phil. Prin. of Phren. p. 52. 4 Phren. Jour. iv.

308.

5 Phrenology, p. 131.

428 APPENDIX.

Hope, Marvellousness, Ideality, Mirthfulness or Gayness, and Imitation,

To Dr Spurzheim's division of the affective faculties into Propensities, or mere tendencies to certain modes of action,-and Sentiments, which are propensities with emotions superadded,-I offer no objection, except that, as will be shewn in the sequel, a third genus ought to be introduced. But when the claims of the individual faculties to be ranked in one or other of the subdivisions are narrowly scrutinized, I fear that much inaccuracy becomes apparent.

Judging from the present state of our knowledge of the fundamental powers of the mind, the whole of the affective faculties, with the exception of only five, seem entitled to be called sentiments, taking that word as it is defined by Dr Spurzheim. These five exceptions I conceive to be-1st, Constructiveness, which is understood to be a mere inclination or tendency to fashion or-configurate, without, so far as I can see, any special emotion superadded to it ; 2dly, Imitation, which is in exactly the same predicament, though classed as a sentiment by Dr Spurzheim ; and, finally, Love of Approbation, Hope, and Ideality, which appear to be mere special emotions, superadded to no propensity whatever. Except these five, I repeat, the whole affective faculties seem to be propensities, tendencies, or inclinations, having emotions annexed to them. This position it will be proper to demonstrate in detail. In taking a survey of the faculties, I shall notice, first, the sort of actions to which they give a tendency ; and, secondly, the simple affections or emotions by which that tendency is accompanied.

Amativeness includes both a tendency to act in a particular way, and a concomitant emotion. The former is the tendency to propagate, and inclination to acts of dalliance in general ; while the latter is the emotion of sexual love. This faculty, therefore, falls within Dr Spurzheim's definition of a sentiment.

Of Philoprogenitiveness the same is true. The tendency is an inclination to associate with children, and the emotion is love of young.

Adhesiveness is a tendency to associate with our fellow-creatures generally, and the corresponding emotion is love or attachment between friends. This emotion never exists except in combination with a desire to be in the society of the person beloved.

The next faculty is usually named Combativeness ; but, for

APPENDIX. 429

reasons elsewhere published,1 I conceive that Opposiveness is a more accurate term. The propensity is not in all cases a tendency to fight, but a general inclination to oppose. The emotion of which the mind is conscious when this tendency acts, is boldness or courage.

Destructiveness is a tendency to injure. The superadded emotion has no name that I am aware of, except when high in the scale of quantitive affections. Ferocity is then the appellation which it receives. The emotion is an ingredient in various compound affections, such as anger, jealousy, malice, and envy. "

Alimentiveness may be regarded as a propensity to eat and drink. Hunger and thirst are not usually referred to this organ ; but these seem to be merely the sentimental affections which accompany the desire to feed.

Secretiveness is an inclination to conceal. The emotion, like that of Destructiveness, receives a name only when it is strong. Slyness and suspicion are emotions of this faculty in a state of vigorous action.

Acquisitiveness is a tendency to acquire and hoard property. Cupidity or greed is the emotion when it is very powerful.

Constructiveness is a tendency to fashion. As already observed, no special emotion accompanies its activity ; so that it is entitled to be called a propensity in Dr Spurzheim's sense of that word.

Self-esteem is the name of the emotion arising from the organ No. 10. Self-complacency is almost synonymous with it ; and pride is the emotion higher in the scale of quantitive affections of the faculty. The corresponding propensity is a tendency to take the lead, to exercise authority, to attend to self-interest and self-gratification, to prefer one's self to other people.

Love of Approbation is an emotion which assumes the name of vanity when in excess: It seems doubtful whether any propensity accompanies it. Shame is an affection of this power.

Cautiousness is the emotion of wariness, and, when powerful, of fear. The propensity is, to take precautions against danger.

Benevolence is surely not less a propensity than Destructiveness, and no reason appears why they should be classified differently. It is a tendency to increase the enjoyment and diminish the misery of sentient beings. The emotions accompanying this tendency are good-will and compassion.

1 See Phren. Journ. vol. ix. P. 147.

430 APPENDIX.

Veneration is a propensity to act with deference, submission, or respect, towards our fellow-men,-to obey those in authority, and to worship the Supreme Being. The emotion is well expressed by the words veneration and deference, and when in great vigour is called devotion.

Firmness I consider to be a tendency to persist in conduct, opinion, and purpose. Resolution is the name which its emotion receives.

Conscientiousness seems to be a propensity to give every man his due. The emotion is the sentiment of justice ; and the actions prompted by it are honest, candid, just.

Hope is a mere emotion, unaccompanied by any propensity. It can hardly be said to give rise, except indirectly, to a tendency to act in a speculative manner. Acquisitiveness, modified by the emotion of Hope, appears to do this.

With Ideality no propensity appears to be connected. There is only the lively emotion of the beautiful and sublime.

Wonder is clearly an emotion, but whether no inclination is associated with it may perhaps be doubted. Is it not, for example, a propensity to exaggerate ?

The emotion of the ludicrous is accompanied by a propensity to act comically.-Imitation is a mere propensity, without any special emotion whatever.

This concludes the list of the affective faculties. If we take the guidance of the principle by which Dr Spurzheim was led, they ought, I think, to be divided into three genera instead of two -the first including those faculties which give rise to tendencies as well as emotions ; the second, those which are tendencies without emotions ; and the third, those which are emotions without tendencies. In the first genus, therefore j we ought to rank Amativeness, Philoprogenitiveness, Adhesiveness, Opposiveness, Destructiveness, Secretiveness, Acquisitiveness, Self-Esteem, Cautiousness, Benevolence, Veneration, Firmness, Conscientiousness, Wonder, and Mirthfulness or the sentiment of the ludicrous. In the second genus-that of tendencies without emotions-I would place Constructiveness and Imitation ; and in the third, comprehending mere emotions, the faculties of Hope and Ideality, and perhaps also Love of Approbation. Such appears to be the classification of the affective faculties, on Dr Spurzheim's principle, warranted by the present state of phrenological science.

No subdivision of the intellectual powers, or those which pro-

APPENDIX. 431

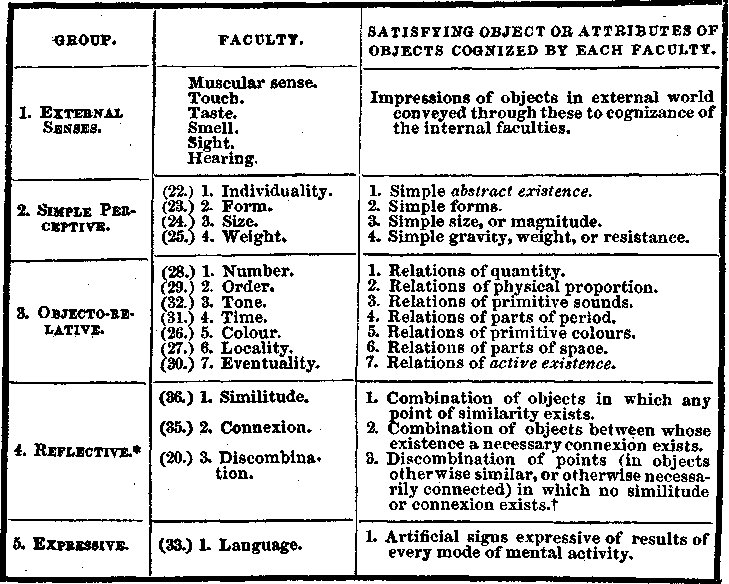

minutely classified them. " They may be subdivided," says he, " into four genera. The first includes the functions of the external senses and of voluntary motion ; the second, those faculties which make man and animals acquainted with external objects and their physical qualities ; and the third, the functions connected with the knowledge of relation between objects or their qualities ;-these three genera I name perceptive faculties. The fourth genus comprises the faculties which act on all the other sensations and notions, and these I style reflective faculties."1 Respecting the first and last of these genera I offer no remarks. The second includes Individuality, Form, Size, Weight, and Colouring, all of which, except Individuality, seem rightly classified. The exception of Individuality is here made on the ground that nothing but the qualities of external objects is perceptible, and that by these alone the existence of an object is revealed to us ; so that Individuality, which takes cognizance of no quality, cannot be said to " perceive" at all. Its essential nature appears to be, as Dr Spurzheim expresses it, " to produce the conception of being or existence, and to know objects in their individual capacities."2 In describing it, Dr Spurzheim studiously avoids the use of the word perception ; he speaks only of conception, knowledge, and cognition.

Under the third genus of intellectual faculties-those " which perceive the relations of external objects"-Dr Spurzheim ranges Locality, Order, Number, Eventuality, Time, Tune, and Language. In some respects he is here in error. Neither Eventuality, Time, nor Language, is cognizant of relations of external objects ; Tune perceives only relations of sounds, and, accordinging to. the best of our present knowledge, Order is merely (what Dr Spurzheim calls it) a " disposition to arrange," and desire to see every thing in its proper place.

In his Philosophical Principles, and Outlines of Phrenology, Dr Spurzheim inconsistently comprehends the second and third genera of the intellectual faculties in one, which is described as embracing the " internal senses or perceptive faculties which procure knowledge of external objects, their physical qualities, and various relations."

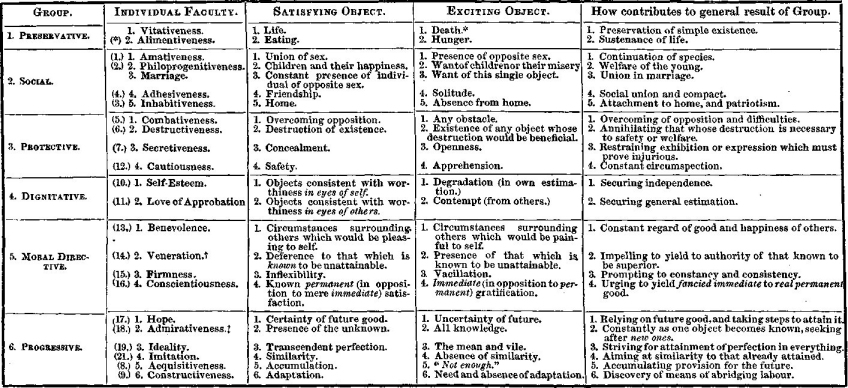

Mr Joshua Toulmin Smith, in his " Synopsis of Phrenology,," (Boston, U. S., 1838), makes some remarks on the classification of the faculties, and presents the results of his reflections in the following tables :-

(432)

" t There is no faculty whose influence is more difficult in a few words to explain, than Veneration, I have done it as well as I was able. The subject will be fully analyzed in my large work, and my definition proved to be correct.

" + + The name given to this faculty I have altered, it being inexpressive of, and misleading as to, the real related objects.

APPENDIX. 433

"From the activity of the propellents alone springs WILL.

II. COMPREHENSIVE POWERS.*

* " The names commonly applied to each faculty in this group are so exceedingly erroneous and misleading, that I have taken the liberty of changing the whole. My reasons will be stated at full in my larger work.

t u That this is the true function of the faculty hitherto termed wit, long and deep investigation has convinced me. The truth of it will be very fully demonstrated in my larger work."

For a farther elucidation of Mr Smith's views, I refer to his work itself.

VOL. II. E

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.