George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

16.-CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

THIS organ is situated on the posterior and lateral parts of the coronal region of the brain, upwards from Cautiousness, and backwards from Hope. In Dr Gall's plates, the function of the part is marked as unascertained, and the merit of the discovery and establishment of the organ is due to Dr Spurzheim. It manifests the love of the true in contradistinction to the false,-of the real in contradistinction to the pretended,-and of the genuine in contradistinction to the factitious. It produces also the feeling of duty, obligation, or incumbency.

The words right and wrong in the English language, have various significations. We say, for instance, that the summing up of an account is right ; in this instance, the word indicates the successful result of the exercise of the organ of Number ;-that a logical conclusion is right, which indicates that we approve of the result attained by the exercise' of Causality and Comparison. In these examples, the word right has a purely intellectual signification. But we say also that it is right to be kind and compassionate, and wrong to be hard-hearted and cruel ; indicating that we approve of the exercise of Benevolence, and disapprove of the action of Self-Esteem and Destructiveness, uncontrolled by compassion. We say that it is right to worship God, and wrong to neglect the expression of our reverence for Him. In these instances, the word right has a moral import. We feel that it is a duty to be benevolent, and a duty also to worship God. The faculties of Benevolence and Veneration, therefore, produce each a distinct moral emotion, attended with the sentiment of duty or incumbency. But there is a third moral emotion different from these, which is manifested by the organ of Conscientiousness. For example, if we call

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 419

upon one person to do us an act of kindness, and on another to pay a debt which he owes us, and if both refuse, the emotions which spring up in our minds are very different in the two cases. In the first instance, we say that the individual was wrong, in not manifesting Benevolence towards us, but we feel that we have no title, natural or legal, to exact compliance : in the latter case, we feel that we have a natural title to do so, and if the statute-book does not afford us also a legal title, we say that it is imperfect. The emotion which arises in the latter case is that which I ascribe to the faculty of Conscientiousness. It springs up in the mind when the exactable rights and incumbent duties of ourselves and others are the subjects of consideration.

The intellectual faculties investigate the qualities and relations not only of external objects, but of the desires and emotions which arise in the mind itself. They, however, do not produce these desires and emotions ; and consequently, unless the special organ on which each of these depends is active, the intellect cannot become acquainted with it. For example, as Causality and Comparison cannot judge of melody unless the organ of Tune be sufficiently developed, neither can they judge of kindness without the co-operation of the organ of Benevolence ; nor, according to my view, can they judge of right, duty, or incumbency in cases where there is a natural title in one party to demand, and a natural obligation on another to perform, without the aid of the organ of Conscientiousness. The intellect alone may judge of legal obligation ; because it is sufficient of itself to discriminate whether " it is so nominated in the bond ;" but without the aid of the organ of Conscientiousness, it cannot arrive at a sound conclusion whether the thing " nominated in the bond" is naturally and intrinsically, irrespective of the bond, incumbent or not incumbent on the party whose signature it bears.

It is the faculty of Conscientiousness, then, which produces the feeling of natural right on the part of one to demand, and of natural obligation on another to perform, for which we have no single definite expression in the English

420 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

language. What is commonly called justice, is the result of this sentiment acting in combination with the intellectual powers, the latter investigating the motives and consequences of the actions, on the justice or injustice of which the mind is to decide ; but they do not feel the peculiar emotion which I have attempted to describe. Persons in. whom the organ of Conscientiousness is very deficient, give. the name of justice to the dictates of Benevolence or Veneration, or to the enactments of the law ; but when the organ is large, the individual not only does not limit his sentiments of obligation by the requirements of the statute-book, but in some instances he will acknowledge that he has no natural title to what the civil law places at his disposal, and in other cases that he lies under a natural obligation to perform what the law does not enforce. In short, he feels within himself an inward law of duty, independently of the dictates of Benevolence and Veneration, and of the terms of statutory enactment. In the words of St Paul, he is a law. unto himself.

I could fill a volume with cases in support of this organ ; but I shall here confine myself to a few.

In 1816, I was requested to find out and engage a person bred to business, accustomed to keep books, of strict integrity, and of an agreeable address, to act as salesman, cashier, and confidential clerk, to a manufacturing company, the business of which, by the death of the proprietor, had devolved on his family, none of whom were, at that time, in a condition to carry it on themselves. Before this occurrence I had attended Dr Spurzheim's lectures, and was slightly acquainted with Phrenology, but had little experience in observing the organs, and, consequently, no reliance on it as a science of practical utility. I proceeded, therefore, in the ordinary way to discover a fit person to fill the situation. At length an individual was recommended to me by a merchant in Edinburgh whom I had long known and esteemed ; and the qualifications ascribed to him were the following. He was nearly thirty years of age, married, an excellent book-keeper, of pleasing address, highly religious, and of the strictest in-

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 421

tegrity. He was at once engaged by my friends, and entered on his duties. He was entrusted with the cash and cash-book ; but every week one of his employers balanced the cash-book, and counted the money on hand, in order so far to keep a check on his honesty.

From the first, I had observed that his organs of Conscientiousness were very deficient, and that Firmness was not large. His intellectual organs were well developed, as were also those of Benevolence and Veneration, while Love of Approbation was very large. I expressed to the gentleman who had recommended him, my regret that his organs of Conscientiousness were so palpably defective ; when he replied that he knew nothing about the effect of the organs, but that he had had experience that Christianity had cured any defects which might originally have existed in the dispositions of the individual, and that he was an honest man. I could not venture to controvert this view, and the person's conduct appeared for several years to confirm it.

He was a leading member of a dissenting congregation, and his house, which was situated within the manufactory, was the resort of his numerous friends for prayer-meetings. The solemn notes of the psalms and hymns which they sang, were often heard resounding through the adjoining apartments in which the operations were carried on. My own impression became strengthened, that a great natural defect might be supplied by other principles ; but in the course of time different views of his character were evolved. His cash-book became confused ; the days for balancing it were postponed by him under a variety of pretences ; the usual returns from the sales began seriously to diminish, and I was led to insist on an investigation of his conduct and transactions. He then came to me in great agitation and prefaced his address with these words : " I am come to acknowledge to you that I am the greatest villain on earth ; you may have me hanged if you please." He then confessed that from a very early period of his employment he had embezzled the funds entrusted to his care, and falsified the entries in his cash-book to conceal his deficiencies, till at last

422 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

the falsifications had become so numerous that he himself was no longer able to discriminate between the real and the fictitious entries.

This case produced a strong impression on my mind of the importance of Phrenology as an indication of natural qualities ; and in examining the details of this individual's delinquencies, the close connection between his conduct and the peculiarities of his cerebral development became still more striking. He confessed freely the use to which he had applied the embezzled money. He was not in the least addicted to sensual debauchery in any form ; but his large Benevolence and Love of Approbation rendered him kind and hospitable, and his first error was that of entertaining his friends at an expense disproportionate to his income, and his second was assisting them in their pecuniary difficulties, with loans of his employer's funds, which were never repaid. These two forms of temptation led him into embezzlements to the extent of four or five hundred pounds. He then became alarmed at the prospect of detection, and, as the state lottery was then existing, he purchased tickets in it to a large amount, and, as he stated to me, he prayed fervently that they might become prizes-not from any desire for the money for his own sake, but that he might be enabled, by an act of Providence, to escape from the pit into which he had fallen. All the tickets turned up blanks, and his acknowledged deficiencies amounted to L.600 at the time when the avowal was made.

I could not avoid the conclusion that this sacrifice of character on his part, and of property on the part of his employer, was, to a great extent, the consequence of having exposed him to temptations which his natural qualities were not calculated to resist ; and he was not prosecuted. His previous employer had not entrusted money to him confidentially, and had not been cheated. He was, therefore, dismissed with a solemn admonition not to belie his Christian character in future ; but I regret to add, that his subsequent life afforded no indications of moral amendment. He entered into trade on his own account, and after one or

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 423

two bankruptcies left Edinburgh, and I heard of him in the United States still living by the practice of plausibilities and falsehood.

From that time forward, I directed much attention to the connection between practical conduct and particular combinations of the cerebral organs. I not only visited prisons, but adopted the rule not to engage domestic servants without examining their heads.

At the time when I became a phrenologist, I had in my employment individuals in whom the organs of Conscientiousness were deficient, and I did not on this account dismiss them from my service. One of them had a large development of the intellectual organs, large Benevolence, large Self-Esteem and Love of Approbation, moderate Veneration, large Secretiveness and Acquisitiveness, but with very deficient Conscientiousness. Through motives of benevolence, I retained him in my employment ; but notwithstanding a vigilant superintendence which I exercised over his conduct, I was repeatedly cheated and plundered of sums of money by him. Another, in whom the same combination of organs occurred, but with the addition of large organs of the animal propensities, quitted my service for a situation of higher emolument, but in which he was left more to the guidance of his own faculties than with me : He fell a victim to "his moral deficiencies, was dismissed, lost his character and condition in society, and lived to become a dissipated beggar, on whom his former equals bestowed pence and old clothes. After I began to apply Phrenology practically, I wished to hire a lad as a stable boy :-one of 13 or 14 years of age was highly recommended to me by a woman from the country, whom I had long known and respected equally for her sound discrimination and integrity. She said that he was the son of a neighbour of hers, that she had known him from his infancy, and that I might rely on his moral qualities as well as on his knowledge of horses. On examining his head, I found the intellectual organs, and those of Benevolence, Veneration, and Firmness, to be well developed ; but Secretiveness and Acquisitiveness were both

424 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

large, while Conscientiousness was very deficient. "Without assigning any particular reason, I told the woman that the boy would not suit me ; and she left my house in high indignation (which she loudly expressed to some of the members of my family), that " I should reject honest men's sons from my service because their heads did not please me !" In about a month, she returned, and said-" Oh, Sir, I am ashamed to face you again, after all I have said against you about that boy;" and she proceeded to mention that since her last visit, she had learned that the lad had been dismissed from his last place on account of thieving, and that his character was known, in the part of the country where he had served, as that of a thief, although she had never entertained the least suspicion of the fact, she having been acquainted with him only while living with his parents, and his place of service having been ten or twelve miles distant from their and her own residence.

Several years ago, a man of education and talent who held civic and ecclesiastical offices in Edinburgh, was noted for the active interest which he took in missionary societies and other schemes for the promotion of religion. In him the organs of the intellectual faculties, and also those of Benevolence, Veneration, Firmness, Self-Esteem, Cautiousness, Secretiveness, and Amativeness, were large ; but that of Conscientiousness was very deficient. After nearly thirty years of ostensible piety and respectability, it was discovered that he had all along been deviating widely from the paths of rectitude ; and dishonesty and licentiousness were the two conspicuous features of his delinquency.

Another individual, also a man of talent and education, to a good intellectual endowment added large organs of Benevolence, Veneration, and Love of Approbation, with very deficient organs of Cautiousness, Conscientiousness, and Firmness. He was generous and obliging to excess, and reckless of justice. He borrowed money from all who would lend him ; pledged his faith most positively to each lender to repay his sum on a particular day, and never thought more of the promise, until he was dunned or compelled

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 425

to perform. The proverbial expression of robbing Peter to pay Paul was so far realized in his practice, that he often borrowed from Peter to lend to Paul, but although Paul repaid him, he did not always refund to Peter.

These cases, to which I could add many more, serve to indicate that the sentiment of justice does not arise from Benevolence, Veneration, and Intellect. On the other hand, a lady, a near relative of mine, to an excellent developement of the intellectual organs, added large organs of Destructive-ness, Veneration, Conscientiousness, and Firmness, but with moderate Benevolence. She was severe and stern in her manners, sentiments, and judgments, but scrupulously just ; that is to say, she brought every action of herself and others to the rigid standard of absolute right to exact, and of obligation to perform ; and was little disposed to grant indulgences or to make allowances for failures, omissions, and shortcomings. She was a strict Calvinist, and derived great consolation from her religious faith. In another lady, with whom I was intimately acquainted for twenty years, the organs of Conscientiousness and Firmness were very large, that of Love of Approbation was large, while an average intellect was combined with moderate Secretiveness and Benevolence. She also was distinguished for trying every action and opinion by the standard of rigid justice. So powerful was this sentiment in her mind, that she could never conceive how any persons could be offended by having the naked truth stated to them, and she was accustomed to express openly to her friends the freest opinions of their shortcomings and imperfections. On the other hand, she was never offended by the plainest remarks respecting her own conduct, if addressed to her respectfully, and in the spirit of truth.

After more than thirty years' experience of the world in actual life, and in various countries, I cannot charge my memory with an instance in which I have been permanently treated unjustly by an individual in whom the organs of Conscientiousness and intellect were largely developed : a momentary act of injustice may have been done, through misapprehension or irritation ; but after correct information

426 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

has been furnished, and excited feelings have been allowed time to cool, I have found persons so endowed, ever disposed to act on the dictates of Conscientiousness. When, through similar causes, I have been led unintentionally to do them wrong, I have found them, on proper explanations, equally ready to be satisfied with justice. By persons so organized, I have never been maltreated on account of my differing from them in opinion, even when they dissented most widely from my views. Such individuals, when they combated my statements, represented them fairly, and met them by honest argument. On the other hand, I have been assailed by some opponents, who have not scrupled to use falsehood, misquotation, and misrepresentation, as weapons of attack. In their heads I have uniformly observed the organ of Conscientiousness to be deficient.

The dispute among philosophers about the existence of moral sentiments in the human mind, is of very ancient standing, and it has been conducted with great eagerness since the publication of the writings of Hobbes in the middle of the seventeenth century. This author taught, " That we approve of virtuous actions, or of actions beneficial to society, from self-love ; because we know, that whatever promotes the interest of society, has on that very account an indirect tendency to promote our own." He farther taught, that, " As it is to the institution of government we are indebted for all the comforts and the confidence of social life, the laws which the civil magistrate enjoins are the ultimate standards of morality."1

Cudworth, in opposition to Hobbes, endeavoured to shew that the origin of our notions of right and wrong is to be found in a particular power of the mind, which distinguishes truth from falsehood.

Mandeville, who published in the beginning of the last century, maintained, as his theory of morals, That by nature man is utterly selfish ; that, among other desires which he likes to gratify, he has received a strong appetite for praise ;

1 Stewart's Outlines, p. 128.

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 427

that the founders of society, availing themselves of this propensity, instituted the custom of dealing out a certain measure of applause for each sacrifice made by selfishness to the public good, and called the sacrifice Virtue. " Men are led, accordingly, to purchase this praise by a fair barter ;" and the moral virtues, to use Mandeville's strong expression, are " the political offspring which flattery begot upon pride" And hence, when we see virtue, we see only the indulgence of some selfish feeling, or the compromise for this indulgence in expectation of some praise.1

Dr Clarke, on the other hand, supposes virtue '' to consist in the regulation of our conduct, according to certain fitnesses which we perceive in things, or a peculiar congruity of certain relations to each other ;'' and Wollaston, whose views are essentially the same, " supposes virtue to consist in acting according to the truth of things, in treating objects according to their real character, and not according to a character or properties which they truly have not."2

Mr Hume, it is well known, wrote an elaborate treatise, to prove, " that utility is the constituent or measure of virtue ;'' in short, to use the emphatic language of Dr Smith, " that we have no other reason for praising a man, than that for which we commend a chest of drawers."3.,

There is another system " which makes the utility according to which we measure virtue, in every case our own individual advantage.'1 Virtue, according to this system, is the mere search of pleasure, or of personal gratification. " It gives up one pleasure, indeed, but it gives it up for a greater. It sacrifices a present enjoyment ; but it sacrifices it only to obtain some enjoyment, which, in intensity or duration, is fairly worth the sacrifice." Hence, in every instance in which an individual seems to pursue the good of others, as good, he seeks his own personal gratification, and nothing else.4

1 Fable

of the Bees, vol. i. p. 28-38. 8vo. London, 1728 ; and Brown's

Lectures, vol. iv. p. 4. 2 Brown's Lectures, vol. iv. p.

17.

3 Brown's Lectures, vol. iv. p. 32. 4 Id. p. 64.

428 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

Dr Hutcheson, again, strenuously maintains the existence of a moral sense, on which our perceptions of virtue are founded, independently of all other considerations.

Dr Paley, the most popular of all authors on moral philosophy, does not admit a natural sentiment of right and wrong as the foundation of virtue, but is also an adherent of the selfish system, under a modified form. He makes virtue consist in " the doing good to mankind, in obedience to the will of God, and for the sake of everlasting happiness."1 According to this doctrine, " the will of God is our rule, but private happiness our motive ;" which is just selfishness in another form.

Dr Adam Smith, in his Theory of Moral Sentiments, endeavours to shew, that the standard of moral approbation is sympathy, on the part of the impartial spectator, with the action and object of the party whose conduct is judged of.

Dr Reid, Lord Kames, and Mr Stewart, maintain the existence of a faculty in man, which produces the sentiment of right and wrong, independently of any other consideration.

Dr Benjamin Rush maintains the existence of a moral faculty, and treats of the influences of physical causes upon it. He regards it as a self-acting emotion. His words are-" It is worthy of notice, that while second thoughts are best in matters of judgment, fir at thoughts are always to be preferred in matters that relate to morality ; second thoughts, in these cases, are generally parlies between duty and corrupted inclinations. Hence, Rousseau has justly said that a well regulated moral instinct is the surest guide to happiness." Rush's Enquiry, p. 13.

These disputes are as far from being terminated among metaphysicians at present, as they were a century ago. A writer on the subject, the author of the article moral philosophy in The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia, disputes the existence of a moral sense, and founds virtue upon religion and

1 Brown's Lectures, vol. iv. p. 10, 101.

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 429

utility. Sir James Mackintosh, in his Dissertation on the progress of Ethical Philosophy, prefixed to the Encyclopædia Britannica, gives an account of conscience which I confess myself unable to comprehend. He speaks of it as formed of " many elements" and by " the combination of elements so unlike as the private desires and the social affections." " It becomes," says he, " from these circumstances, more difficult to distinguish its separate principles, and it is impossible to exhibit them in separate action." (P. 409.)

I have introduced this sketch of conflicting theories, to convey some idea of the boon which Phrenology would confer upon moral science, if it could fix on a firm basis this single point in the philosophy of mind,-That, not only are we endowed with sentiments giving rise to disinterested inclination to benefit our fellow creatures, and to reverence goodness and greatness, but moreover, with a power or faculty, the object of which is to produce the feeling of duty and obligation, independently of selfishness, hope of reward, fear of punishment, or any extrinsic motive ; a faculty, in short, the natural language of which is, " Fiat justitia, ruât colum.'' Phrenology does this by a demonstration, founded on numerous observations, that those persons who have the organ of Benevolence large are disposed to perform acts of kindness ; those in whom that of Veneration is large are inclined to reverence, and those whose organ of Conscientiousness is greatly developed experience powerfully the sentiment of justice ; while those who have the parts in question small, are little alive to the corresponding emotions. This evidence is the same in kind as that adduced in support of the conclusions of physical science.

Conscientiousness, when aided by enlightened intellect, is of the very highest importance as a regulator of all the other faculties. When they tend to overstep, or fall below, the limits of justice, it furnishes the curb or applies the spur. If Combativeness and Destructiveness be boo active, Conscientiousness then prescribes a limit to their indulgence ; it permits defence, but no malicious aggression : if Acquisitive-

430 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

ness urge too keenly, it reminds us of the rights of others : if Benevolence tend towards profusion, this faculty issues the admonition, Be just before you are generous : if Ideality aspire to its high delights, when duty requires laborious exertions in an humble sphere, Conscientiousness supplies the curb, and bids the soaring spirit restrain its wing. If Acquisitiveness be too feeble to prompt to industry, this combination of powers calls aloud on us to labour, that we may do justice to those towards whom we lie under obligations. In these results, I consider the feeling of duty, obligation, or incumbency, to arise from Conscientiousness. From this regulating quality, Conscientiousness is an important element in constituting a practical judgment and an upright and consistent character. Hence its cultivation in children is of great importance.l

When this faculty is powerful, the individual is disposed to regulate his conduct by the nicest sentiments of justice : there is an earnestness, integrity, and directness in his manner, which inspire us with confidence, and give us a conviction of his sincerity. Such an individual desires to act justly from the love of justice, unbiassed by fear, interest, or any sinister motive.

The activity of Conscientiousness takes a wider range than regard merely to the legal rights and property of others. It prompts those in whom it is strong, to do justice in judging of the conduct, the opinions, and the talents of others. Such persons are scrupulous, and as ready to condemn themselves as to find fault with others. When predominant, it leads to punctuality in keeping appointments, because it is injustice to sacrifice the time and convenience of others, by causing them to wait till our selfishness finds it agreeable to meet them. It prompts to ready payment of debts, as a piece of justice to those to whom they are due. It will not permit even a tax-collector to be sent away unsatisfied, from any cause except inability to pay ; because it is injustice to him,

1 Much attention is paid to the training of Conscientiousness in the Infant Schools of Mr Wilderspin. See Phren. Journ. vi. 429.

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 431

as it is to clerks, servants, and all others, to require them to consume their time in unnecessary solicitation of what is justly due and ought at once to be paid. It leads also to great reserve in making promises, but to much punctuality in performing them. When combined with a favourable development of other organs, it gives consistency to conduct ; because, when every sentiment is regulated by justice, the result is that " daily beauty in the life " which renders the individual in the highest degree amiable, useful, and respectable. It communicates a pleasing simplicity to the manners, which commands the esteem, and wins the affection, of all well-constituted minds.

In practical life, when it predominates over Benevolence, it renders the individual a strict disciplinarian, and a rigid, although a just, master. It disposes him to invest all actions with a character of duty or obligation, so that if a servant misplace any article, it is not simply an error, but a fault. Some very estimable persons, by giving way to this tendency in matters of trivial importance, render themselves not a little disagreeable.

A deficiency of Conscientiousness produces effects exactly opposite. The weakness of the faculty appears in the general sentiments of the individual, although circumstances may place him beyond the reach of temptation to infringe the law. The predominant propensities and sentiments then act without this powerful regulator. If Adhesiveness and Benevolence attach him to a friend, he is blind to all his imperfections, and extols him as the most matchless of human beings. If this model of excellence happen to offend, he becomes a monster of ingratitude and baseness ; he passes in an instant from an angel to a demon. Had Conscientiousness been large, he would have been viewed all along as a man ; esteem towards him would have been regulated by principle, and the offence candidly dealt with. If Love of Approbation be large, and Conscientiousness deficient, the former will prompt to the adoption of every means that will please, without the least regard to justice and propriety. If an individual have a weak point in his character. Love of

432 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS-

Approbation will then lead to flattering it ; if he have extravagant expectations, it will join in all his hopes ; if he be displeased with particular persons, it will affect to hate with his hatred, altogether independently of justice. In short, the individual in whom this faculty is deficient, is apt to act and also to judge of the conduct of others, exactly according to his predominant sentiments for the time : he is friendly when, under the impulse of Benevolence, and severe when Destructiveness predominates : he admires when his pride, vanity, or affection, gives him a favourable feeling towards others ; and condemns when his sentiments take an opposite direction ; always unregulated by principle. He is not scrupulous, and rarely condemns his own conduct, or acknowledges himself in the wrong. Minds so constituted may be amiable, and may display many excellent qualities ; but they are never to be relied on where justice is concerned. As judges, their decisions are unsound ; as friends, they are liable to exact too much and perform too little ; as sellers, they are prone to misrepresent, adulterate, and overcharge-as buyers, to depreciate quality and quantity, or to evade payment.

The laws of honour, as apprehended by some minds, are founded on the absence of Conscientiousness, with great predominance of Self-Esteem and Love of Approbation. If a gentleman is conscious that he has unjustly given offence to another, it is conceived by many that he will degrade himself by making an apology ; that it is his duty to fight, but not to acknowledge himself in fault. This is the feeling produced by powerful Self-Esteem and Love of Approbation, with great deficiency of Conscientiousness. Self-Esteem is mortified by an admission of fallibility, while Love of Approbation suffers under the feeling that the esteem of the world will be lost by such an acknowledgement ; and if no higher sentiment be present in a sufficient degree, the wretched victim will go to the field and die in support of conduct that is indefensible. When Conscientiousness is strong, the possessor, when he is aware that he is in the wrong, feels it no degradation to acknowledge himself in fault : in fact, he rises

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 433

in his own esteem by doing so, and knows that he acquires the respect of well constituted minds ; while, if fully conscious of being in the right, there is none more inflexible than he. This sentiment is essential to the formation of a truly philosophic mind, especially in moral investigations. It produces the desire of discovering truth, the tact of recognising it when discovered, and that perfect reliance on its invincible supremacy, which gives at once dignity and peace to the mind. A person in whom Conscientiousness, Benevolence, and Veneration are deficient, views moral propositions as mere opinions ; esteems them exactly as they are fashionable or the reverse, and cares nothing about the evidence on which they are based. Self-Esteem and Secretiveness, joined with deficiency of this sentiment, lead to paradox ; and if Combativeness be added, there will be a tendency to general scepticism, and the denial or disputation of the best-established truths on every serious subject. No sentiment is more incomprehensible to those in whom the organ is small, than Conscientiousness. They are able to understand conduct proceeding from ambition, self-interest, revenge, or any other inferior motive ; but that determination of soul, which suffers obloquy and reproach, nay death itself, from the pure and disinterested love of truth, is to them utterly unintelligible. They regard it as a species of insanity, and look on the individual as " essentially mad, without knowing it." Madame de Staël narrates of Bonaparte, that he never was so completely at fault in his estimate of character, as when he met with opposition from a person actuated by the pure principle of integrity alone. He did not comprehend the motives of such a man, and could not imagine how he might be managed. The maxim, that " every man has his price," will be regarded as profoundly discriminative by those in whom Acquisitiveness or Love of Approbation is very large, and Conscientiousness moderate ; but there are minds whose deviation from the paths of rectitude no price can purchase, and no honours pro-

434 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

cure ; and those in whom Conscientiousness, Firmness, and Reflection, are powerful, will give an instinctive assent to the truth of this proposition.

I have observed that individuals in whom Love of Approbation was large, and Conscientiousness not in equal proportion, were incapable of conceiving the motive which could lead any one to avow a belief in Phrenology, while the tide of ridicule ran unstemmed against it. If public opinion should change, such persons would move foremost in the train of its admirers : They instinctively follow the doctrines that are most esteemed from day to day ; and require our pity and forbearance, as their conduct proceeds from a great moral deficiency, which is their misfortune rather than their fault.

The fact that this organ is occasionally deficient in individuals in whom the organs of intellect are amply developed, and the animal propensities strong, accounts for the unprincipled baseness and moral depravity exhibited by some men of unquestionable talents. It is here, as in other cases, of the greatest importance to attend to the distinct functions of the several faculties of the mind. No mistake is more generally committed than that of conceiving, that, by exercising the faculty of Veneration, we cultivate those of Benevolence and Justice : but if Veneration be large, and Conscientiousness small, a man may be naturally disposed to piety and not to justice ; or if the combination be reversed, he may be just and not pious, in the same manner as he may be blind and not deaf, or deaf and not blind. Deficiency of Veneration, as before observed, does not necessarily imply profanity ; so that, although an individual will scarcely be found who is profane and at the same time just, yet many will be found who are just and not pious, and vice versa.

Conscientiousness, when powerful, is attended with a sense of its own paramount authority over every other faculty, and it gives its impulses with a tone which appears like the voice of Heaven. The scene in The Heart of Mid-Lothian, in which Jeanie Deans is represented giving evidence on her sister's trial at the bar of the High Court of Justiciary, af-

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 435

fords a striking illustration of its functions and authority when supported by piety. A strong sense of the imperious dictates of Conscientiousness, and of the supreme obligation of truth, leads her to sacrifice every interest and affection which could make the mind swerve from the paths of duty ; and we perceive her holding by her integrity, at the expense of every other feeling dear to human nature.

Repentance, remorse, a sense of guilt and demerit, on account of unjust actions, are the consequences of this faculty. It is a mistake, however, to suppose, that great criminals are punished by the accusations of conscience ; for this organ is generally very deficient in men who have devoted their lives to crime, and, in consequence, they are strangers to the sentiment of remorse. Haggart felt regret for having murdered the jailor at Dumfries, but no remorse for his thefts. His large Benevolence induced the uneasy feeling on account of the first crime, and his small Conscientiousness was the cause of his indifference to the second. If Conscientiousness had been strong, he could not have endured the sense of the accumulated iniquities with which his life was stained. In Bellingham, both Benevolence and Conscientiousness were small, and he manifested equal insensibility to justice and mercy, and testified no repentance or remorse.

Dr Gall did not admit a faculty and organ of Conscientiousness. He formerly considered remorse as the result of the opposition of particular actions to the predominant dispositions of the individual ; and, according to him, there are as many consciences as faculties. For example, if a person in whom Benevolence was large, injured another, this faculty would be grieved ; and the feeling so arising, he considered to be regret or repentance. If a usurer or a libertine neglected an opportunity, he would repent, the former for not having gratified Acquisitiveness, the latter for not having seduced some innocent victim. Dr Gall called this natural conscience, and said that we could not trust to it, and that hence laws and positive institutions become necessary. Dr

436 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

Spurzheim answered this argument in an able manner, and shewed that the mere feeling of regret is totally different from that of remorse. "We may regret that we lost a pair of gloves, or spent half-a-crown ; but this feeling bears no resemblance to the upbraidings of conscience for having robbed a neighbour of his right, committed a fraud, or uttered a malevolent falsehood. Dr Gall latterly regarded Benevolence as the moral faculty : but the sentiment of duty and incumbency, where the rights of others are concerned, is as clearly distinguishable from mere goodness or kindness, as hope is from fear ; and, besides, positive facts prove that the two feelings depend on different organs.

"When this organ is deficient, and Secretiveness large, and especially when the latter is aided by Ideality and Wonder» a natural tendency to lying is produced, which some individuals, who have possessed the advantages of education and moved in good society, have never been able to overcome.

Some criminals, on being detected, confess, and seem to court punishment as the only means of assuaging the remorse with which their minds are devoured. The Phrenological Society has a cast of the skull of one person who displayed this desire to atone for his crime. It is that of John Rotherham, who met a servant-girl on the highway and murdered her, out of the pure wanton impulse of Destructiveness ; for he did not attempt to violate her person ; and, of her property, he took only her umbrella and shoes. When apprehended, he confessed his crime, insisted on pleading guilty, and with great difficulty was induced by the judge to retract his admission. The organ is large in him. He appears to have acted under the influence of excessive Destructiveness. James Gordon, on the contrary, who murdered a pedlar boy in Eskdale Muir, stoutly denied his guilt, and, after conviction, abused the jury and judge for condemning him. Before his execution, however, he admitted that his sentence was just. In him, the organ of Conscientiousness is defective.

The organ is very large in Mr H., the Rev. Mr M., Dr Hette, and Rammohun Roy, who all manifested the senti-

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 437

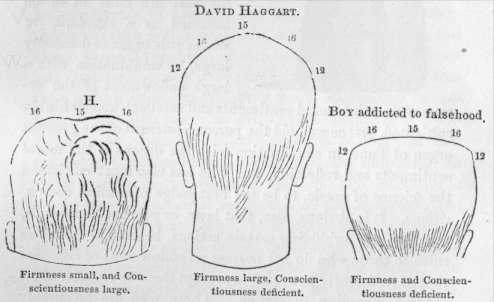

ment powerfully. Considerable attention is requisite to discriminate accurately the size of this organ. When Firmness is large and Conscientiousness small, the head slopes at an acute angle downwards from Firmness, as in Haggart and King Robert Bruce. When both Firmness and Conscientiousness are large, the head rises considerably from Cautiousness to Firmness, with a full and rounded swell, as in the Rev. Mr M., p. 184. When both of these organs are small the head rises very little above Cautiousness, but runs flat across to Cautiousness on the other side, as in the boy.

In Mrs H., Firmness 15 is small, and Conscientiousness 16 large; in D. Haggart, Firmness 15 is large, and Conscientiousness 16 deficient: and in the boy both of these organs are deficient, which is indicated by the head rising very little above 12 Cautiousness. If in Mrs H. Firmness had been as large as Conscientiousness, or in Haggart Conscientiousness had been as large as Firmness, the heads would have presented a full and elevated segment of a circle passing from Cautiousness to Cautiousness, the very opposite of the flat and low line in the head of the boy. It is of great importance in practice to attend to these different forms.

The difference of development of this organ in different nations and individuals, and its combinations with other organs, enable us to account for the differences in the notions of justice entertained at different times, and by different people.

438 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

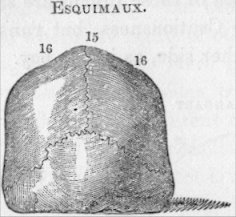

The sentiment of truth is found by the English judges to be so low in the Africans, the Hindoos, and the aboriginal Americans, that such individuals are not received as witnesses in the colonial courts ; and it is a curious fact, that a defect in the organ of Conscientiousness is a reigning feature in the skulls of these nations in the possession of the Phrenological Society.1 It is small likewise in the Esquimaux, who are esquimaux. notoriously addicted to dishonesty and theft.2 The notions of justice of that individual are most fit to be assumed as a standard, in whom this organ is decidedly large, in combination with a large endowment of the organs of the other moral sentiments and intellect, and all highly cultivated, just as we hold the person possessed of the greatest organ of Tune, in combination with the organs of the moral sentiments and reflection, and who has also most cultivated the science of music, to be the best judge of musical compositions. It is obvious, also, that laws, or positive commands, ordering and forbidding certain actions, become necessary as rules to those who do not possess an endowment of this sentiment sufficiently powerful to prompt them to regulate their conduct according to justice. Those. who are favourably gifted, are, in the language of St Paul, " a law unto themselves."

It has been objected, that persons possessing a large development of this organ, not unfrequently act in opposition to the dictates of the sentiment, and practise selfishness, or sacrifice justice to ambition, exactly as those do in whom the organ is small ; and it is asked, What becomes of the organ in such instances 1 The plurality of organs and faculties explains this phenomenon. Conscientiousness is not the only faculty in the mind, and, although it is paramount in authority, it is not always so in activity. A person in whom Be-

1 See Phren. Journ., viii. 515, 530, 581. 2 Id, p. 301.

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 439

nevolence and Destructiveness are both large, may, under special circumstances which strongly excite Destructiveness, manifest that faculty in rage, revenge, or undue severity, in direct opposition to Benevolence. In like manner an individual in whom Acquisitiveness and Self-Esteem are large, may, if these are very forcibly addressed, obey their impulses in opposition to that of Conscientiousness. But the benevolent man, when the temptation is past, feels the opposition between his conduct and the dictates of Benevolence ; and, in like manner, the individual here supposed, on cool reflection, becomes conscious of the opposition between his unjust preference of himself, and the dictates of Conscientiousness : both will repent, and will make atonement, and desire to avoid repetition of such offences. If Benevolence and Conscientiousness were small, they would not feel that their actions were wrong ; they would experience no remorse ; and their lower faculties would operate with greatly increased violence. I have observed in practical life, that when Conscientiousness is large in any individual, he yields compliance to demands made on him whenever a strong case in justice is made out by the applicant ; but when the organ is not large, he is moved only by favour or partiality. It is of the utmost importance to the respectability of Government, and the welfare of the people, that public functionaries should possess the former character. The necessity of it in persons in authority will be more and more felt as society advances in knowledge, discrimination, and morality.

Another difficulty is experienced in the doctrine, that Conscientiousness is merely a sentiment, and does not by itself lead to the perception of justice. This will be best removed by an example. A judge hears one side of a cause, and Conscientiousness, acting on the statement presented to it through the medium of the intellect, produces the feeling that the demands of this party are just. The other litigant is heard, new facts appear, and Conscientiousness may now produce the feeling that justice lies on his side. If this fa-

440 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

eulty itself had formed specific ideas of what is just, it would have been an intellectual power, and reasoning would have been in proportion to it, which is not the case ; but, as it is only a sentiment, its real function is to produce an emotion of justice or injustice, on any particular case or assemblage of facts being presented to it by the intellect. In judicial trials, we do not find Conscientiousness producing opposite emotions on the same case ; but the intellect presenting different cases, or different views of the same case, and Conscientiousness producing its peculiar emotion in regard to each, according as it is laid before it. In framing laws or rules of justice, not only is a powerful intellect necessary to penetrate into the relations of actions, but a good endowment of all the organs of the propensities and sentiments, is also indispensable to furnish the understanding with adequate knowledge of the fundamental impulses and emotions on which it must reason and decide.

In my work on " Moral Philosophy,"1 to which I beg leave to refer, I have stated the qualities which constitute actions virtuous or vicious, and also the theory of merit.

The organ of Conscientiousness is occasionally found diseased, and then the most awful sentiments of guilt, generally imaginary, harrow up the mind. I have seen two individuals labouring under this disease. One of them believed himself to be in debt to an enormous amount, which he had no means of paying ; the other imagined himself to be guilty of murder, and of every variety of wickedness contained in the records of iniquity ; whereas, in fact, the whole conduct of both while in health, has been marked by the greatest humanity, honour, and scrupulosity. When this organ, and that of Cautiousness, are diseased at the same time, the individual imagines himself to be the most worthless of sinners, and is visited with fearful apprehensions of punishment. Such patients sometimes present a picture of despair which is truly appalling. Slight degrees of disease of these organs

*Second Edition, p. 19, et seq.

CONSCIENTIOUSNESS. 441

not amounting to insanity, are not unfrequent in this country, and produce an inward trouble of the mind, which throws a gloom over life, and leads the patient to see only the terrors of religion. Such persons are greatly relieved by being convinced that the cause of their unhappy feeling is disease in the mental organs, and that they may in general be restored to health by proper medical treatment. If they are religiously disposed, their anxiety will probably be directed to their salvation. If they are worldly-minded, the fear of ruin, or of inability to meet their engagements, will probably be the form in which the disease will appear. In all cases, however, where there are no-adequate external causes for the impressions, they may be regarded as really arising from disease of the mental organs, the feelings only being differently directed, according to the character of each individual. I have known great injury done to the health, by treating these depressions, when they occurred in amiable persons, on exclusively religious principles ; and very respectfully, but earnestly, recommend to the friends of such patients to call in a physician as well as a clergyman for their relief.1

In the first edition of this work, I stated that gratitude probably arises from this faculty ; but Sir G. S. Mackenzie, in his Illustrations of Phrenology', has shewn that gratitude is much heightened by Benevolence,-a view in which I now fully acquiesce.

It is premature to speak of the combinations of the faculties, before we have finished the detail of the simple functions ; but this is the most proper occasion, in other respects, to observe, that Phrenology enables us to account for the origin of the various theories of morals before enumerated.

Hobbes, for instance, denied every natural sentiment of justice, and erected the laws of the civil magistrate into the standard of morality. This doctrine would appear natural and sound to a person in whom Conscientiousness was very feeble ; who never experienced in his own mind a single emo-

1 See Dr A. Combe's Observations on Mental Derangement, pp. 187, 196.

442 CONSCIENTIOUSNESS.

tion of justice, but who was alive to fear, to the desire of property, and to other affections which would render security and regular government desirable. It seems to me probable that Hobbes was so constituted.

Mandeville makes selfishness the basis of all our actions, but admits a strong appetite for praise ; the desire for which, he says, leads men to abate other enjoyments for the sake of obtaining it. If we conceive Mandeville to have possessed a deficient Conscientiousness, and a large love of Approbation, this doctrine would be the natural product of his mind.

Mr Hume erects utility, to ourselves or others, into the standard of virtue ; and this would be the natural feeling of a mind in which Benevolence and Reflection were strong, and Conscientiousness weak.

Paley makes virtue consist in obeying the will of God, as our rule, and doing so for the sake of eternal happiness as the motive. This is the natural emanation of a mind where the selfish or lower propensities are considerable, and in which Veneration is strong, and Conscientiousness not remarkable for vigour.

Cudworth, Hutcheson, Reid, Kames, Stewart, and Brown,1

1 I embrace this opportunity of paying an humble tribute to the talents of the late Dr Thomas Brown. The acuteness, depth, and comprehensiveness of intellect displayed in his works on the mind, place him in the highest rank of philosophical authors ; and these great qualities are equalled by the purity and vividness of his moral perceptions. His powers of analysis are unrivalled, and his eloquence is frequently splendid. His Lectures will remain a monument of what the human mind was capable of accomplishing, in investigating its own constitution, by an imperfect method. In proportion as Phrenology shall become known, the admiration of his genius will increase ; for it is the highest praise to say, that in regard to many points of great difficulty and importance in the Philosophy of Mind, he has arrived, by his own reflections, at conclusions harmonizing with those obtained by phrenological observation. Of this, his doctrine on the moral emotion discussed in the text, is a striking instance. Sometimes, indeed, his arguments are subtle, his distinctions too refined, and his style circuitous ; but the phrenologist will pass lightly over these imperfections, for they occur only occasionally, and arise from mere ex-

HOPE. 443

on the other hand, contend most eagerly and eloquently for the existence of an original sentiment or emotion of justice in the mind, altogether independent of other considerations ; and this is the natural feeling of persons in whom the faculty is powerful. A much respected individual, in whom this organ is predominantly large, mentioned to me, that no circumstance in philosophy occasioned to him greater surprise, than the denial of the existence of a moral faculty ; and that the attempts to prove it appeared to him like endeavours to prop up, by demonstration, a self-evident axiom in mathematical science.

In the Phren. Journ. vol. xv. p. 367, a case is mentioned in which the organ was excited by Mesmerism.

The organ is regarded as established.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

© John van Wyhe 1999-2011. Materials on this website may not be reproduced without permission except for use in teaching or non-published presentations, papers/theses.