George Combe's A System of Phrenology, 5th edn, 2 vols. 1853.

Vol. 1: [front

matter], Intro, Nervous

system, Principles of Phrenology, Anatomy of the brain, Division of the faculties 1.Amativeness 2.Philoprogenitiveness 3.Concentrativeness 4.Adhesiveness 5.Combativeness 6.Destructiveness, Alimentiveness, Love of Life 7.Secretiveness 8.Acquisitiveness 9.Constructiveness 10.Self-Esteem 11.Love

of Approbation 12.Cautiousness 13.Benevolence 14.Veneration 15.Firmness 16.Conscientiousness 17.Hope 18.Wonder 19.Ideality 20.Wit or Mirthfulness 21.Imitation.

Vol. 2: [front

matter], external senses, 22.Individuality 23.Form 24.Size 25.Weight 26.Colouring 27.Locality 28.Number 29.Order 30.Eventuality 31.Time 32.Tune 33.Language 34.Comparison, General

observations on the Perceptive Faculties, 35.Causality, Modes of actions of the faculties, National

character & development of brain, On the

importance of including development of brain as an element in statistical

inquiries, Into the manifestations of the animal,

moral, and intellectual faculties of man, Statistics

of Insanity, Statistics of Crime, Comparative

phrenology, Mesmeric phrenology, Objections

to phrenology considered, Materialism, Effects

of injuries of the brain, Conclusion, Appendices: No. I, II, III, IV, V,

[Index], [Works of Combe].

134

ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN.

As already remarked, it is not indispensably necessary, although it is highly advantageous, to become acquainted with the structure of the brain, in order to become a practical Phrenologist. I shall, therefore, here present a brief outline of the structure, so far as a popular reader may be supposed to be interested in it.

The nervous system, as already remarked, is composed of various nervous centres, each possessed of peculiar powers ; and we have divided these centres into the two great divisions of the physical and mental nervous systems. The former comprehends all the so-called spinal centres, which are formed to respond directly to the influence of physical stimuli applied to the peripheral expansions of the nerves, and to execute the behests of the mind ; while the latter elaborates the sensations received from the spinal centres into

ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN. 135

mental perceptions,

forms emotions and thoughts, and consciously directs the actions of the body.

The mental nervous system, which comprehends the cerebrum and cerebellum,

acquires its greatest development in man, who accordingly stands at the head

of created beings in this world. The physical nervous system, on the contrary,

acquires a superior development, and corresponding superior powers, in many

of the lower animals. The horse, for instance, has greater motor powers, the

eagle greater powers of sight, the dog of smell, the hare of hearing, and

the bat of common sensation. Still none of these animals equals man in mental

power ; and in accordance herewith we find that in the lower animals, the

physical nervous system bears a much larger proportion to the mental system

than is the case in man. This difference is more observable the lower we descend

in the scale. Thus in the Lamprey the weight of the brain is to that of the

spinal marrow as 100 to 750

In the Triton, . 100 "180

In the Pigeon, . 100 " 30

In Man, . . 100 ., 2

Thus it appears that the functions of each nervous system are manifested strictly in proportion to the development of its parts ; and the strength of the manifestations is, in general, in direct relationship to this development, or, to speak more clearly, to the respective masses.

In proceeding to examine the human brain, the skull may be opened according to the following directions given by Dr Fossati in his translation of the Elements :—" Begin by making a crucial incision in the in teguments, from the front to the occiput, and from the one ear to the other ; then separate and pull down the parts, and also the muscles which cover the temples. If it is desired to preserve the cranium, it must be sawed, by passing the instrument along the frontal bone, the temples, and the middle part of the occipital bone. In the opposite case, it may be broken in a circular direction with the sharp edge of a hammer in order to lift

136 ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN.

up the skull-cap. There is much less risk of injuring the cerebral membranes and the convolutions by blows of a hammer than in making use of the saw, and no alteration of the internal organization ensues from it. When the top has been raised, the dura mater should be cut from each side of the longitudinal sinus, from the front to the back, and transversely from the middle of the superior portion down to the ears. The falx should be detached in the frontal region and turned back. The top of the head should then be made to hang downwards, in such a manner that the palm of the hand may be applied to it and receive the brain. The middle and frontal lobes are easily disengaged. We cut successively the nerves which present themselves, namely, the bulb of the olfactory nerve, the optic nerves, and the motor nerves of the eye ; and the head should be inclined first to the one side and then to the other, in order to cut carefully the tentorium, in removing the hemispheres. After this the nerves and bloodvessels situated under the pons Varolii should be separated, and the spinal marrow cut as low as possible below the great occipital hole. The cerebellum should then be disengaged with the fingers of the one hand, while the whole mass of the brain, which we lift from the skull, is sustained by the other ; care being always taken not to allow any of the parts to be torn."

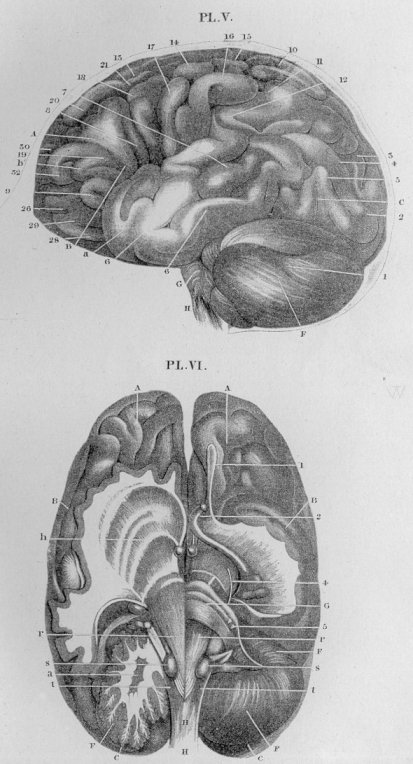

When the brain is laid upon the table, with its base upwards, we observe, in the first place (Plate IV.), the superior portion of the spinal cord, H H, which here receives the name of the medulla oblongata, proceeding upwards, and passing under the arch G G, (called the pons Varolii), to reappear beyond it as two diverging bundles of fibres, which proceed to communicate with the hemispheres of the cerebrum. Their course is more distinctly seen in Plate VI., where the pons Varolii has been removed. The fibres are seen proceeding upwards and outwards, diverging like the framework of a fan. At their superior extremity they combine with some portions of gray matter, to form the striated bodies, h, which consti-

ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN. 137

tute the highest part of the spinal centres, or physical nervous system. It is beyond them that the cerebrum, or true mental brain, commences. In accordance with this remark, it will be observed, that all the nerves (see Plate IV.) rise in the physical system, and that none have their origin in the cerebrum or cerebellum.1 Their functions vary with their origin, some being motor, and others sentient, according as the gray matter from which they spring belongs to the motor or sensory systems. The situation and emergence of the different nerves are seen in Plate IV. The olfactory nerve, 1. appears at the front ; then successively, 2. the optic nerve ; 3. the motor nerve of the eye ; 4. the pathetic nerve ; 5. the trigeminal ; 6. the abductor of the eye ; 7. the facial ; 8. the auditory ; 9. the glosso-pharyngeal ; 10. the vocal ; 11. accessory nerves. G G is the pons Varolii ; H H the medulla oblongata, with (ss) the corpora olivaria, (rr) the corpora pyramidalia, and (tt) the corpora restiformia. See description of Plate IV. for more minute particulars.

The ascending fibres of the spinal system terminate in the striated bodies, and do not pass into the hemispheres of the cerebrum, so that the fibres of the latter (fig. 5) are not the ascending diverging fibres of the spinal system, but the converging descending fibres of the mental system. The fibres of both systems are capable of propagating influences to each other, but are nevertheless to be regarded as distinct structures. The spinal system forms, as it were, an instrument on which the cerebral system plays, and, granting that the physical instrument is perfect, the excellence of the performance will be altogether dependent on the power and capabilities of the cerebrum. The reader will now be in a position fully to understand the results of the experiments of

1 The olfactory nerve may appear to be an exception to this rule, but it differs from all the other nerves in structure in containing gray matter ; and on this account it is regarded by some anatomists as forming a part of the brain. Those who are of this opinion, look upon the nervous bulb within the skull as an olfactory ganglion, and the fibres descending from it to the nostril as the true olfactory nerve.

138 ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN.

M. Flourens,1 which shew that although an animal retains its spinal system intact and the organs of the senses to all appearance uninjured, it neither sees, hears, nor feels, simply because no organ is present to perceive the stimuli which operate on the spinal centres. It is worthy of notice, also, that when the cerebrum is injured, no pain is perceived, although the most acute pain is consequent on injury of the spinal system. This fact, which at first sight appears paradoxical, is readily understood, when it is remembered that,'in the normal condition, no stimuli can reach the brain directly ; they must all pass through the spinal system. Consequently, the substance of the brain is not formed for the purpose of responding to direct physical stimuli, but solely for propagating mental perceptions and emotions. In its normal condition no physical stimulus reaches it directly, but only through the medium of the nerves. When its substance is lacerated by external violence, this is an abnormal influence, to which it does not respond, and no pain is experienced. Reference to Plate VI. will shew that the spinal cord does not all proceed upwards to the cerebrum, but that it gives off lateral branches (tf), called the corpora restiformia, which proceed to the cerebellum. By this means, and also by the pons Varolii, GG, in Plate IV., the cerebellum is placed in intimate connection with the spinal centres, while by means of other fibres, called the commissures of the cerebellum with the cerebrum, (but which are hidden in the Plate by overlying structures), it is placed in communication with the cerebrum.

The cerebrum consists, as already repeatedly mentioned, of two hemispheres, and "each hemisphere," says Dr Fossati, " is divided into three portions, which are named lobes. The anterior lobe (Plate IV., A A) rests on the vault of the orbits, and is separated from the middle lobe by a deep furrow (e e). The middle lobe (B B) is scarcely separated from the posterior (C C). This last is situated partly in the internal tem-

1 Recherches expérimental sur les fonctions du system nerveux.

ANATOMY OF THE BRAIN. 139

poral fossae of the skull, and partly in the tentorium of the cerebellum.

" On all the surfaces of the hemispheres, we perceive convolutions, larger or smaller, and more or less projecting. They are separated from each other by winding furrows called anfractuosities, into which the pia mater descends, while the two other membranes, the arachnoid coat and the dura mater, pass directly over the convolutions, and envelope the whole brain.

" All the parts which compose the brain are double, each part on the one side having a counterpart on the other. They are not exactly symmetrical, one of the sides being in general a little larger than the other. The bundles of the same kind of each side are joined together, and brought into reciprocal action, by transverse nervous fibres, which are called commissures.

" The cerebellum is a nervous mass separated from the hemispheres. It occupies, as we have already observed, the posterior and inferior parts of the cavity of the skull (see Plate V., F). It is enclosed in the space which lies between the transverse fold of the dura mater called the tentorium, and the inferior foss -of the occipital bone. Its form is globular, more extended to the sides than from the front to the back. The furrows which appear on the external surface of the cerebellum are deep ; they closely approach each other, and are not tortuous, as in the brain : The cerebellum has lamince, or leaves, in place of convolutions, which last belong only to the hemispheres."

Such is a brief outline of the anatomy of the brain, and which, though necessarily very imperfect, will be sufficient for our present purpose. The study of the minute anatomy of the brain is one of the utmost difficulty, and requires an amount of time and patience which few are capable of bestowing. The dissection must be performed with the greatest care and attention, on prepared brains, by separating, and carefully scraping, with the flat handle of a scalpel, the parts

140 DESCRIPTION OF THE PLATES.

which should be brought into view. In our description, we have made no reference to many parts of the brain for the simple reason, that any attempt to note minute structure would have merely served to confuse the ideas of the popular student. Several of these structures, however, are noted in the description of the Plates which is subjoined, and for further information the student is referred to anatomical works.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PLATES.1

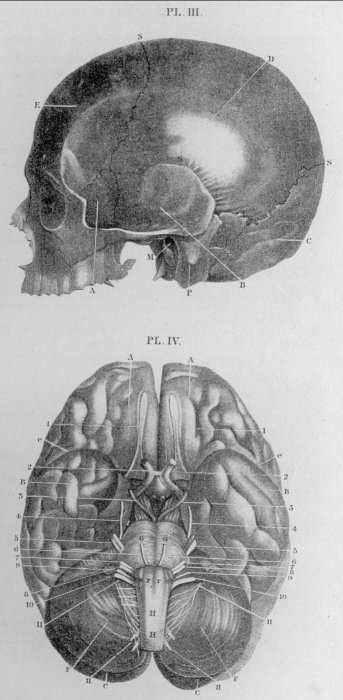

PLATE III.-THE SKULL.

A, Basilar or sphenoid bone-small portion reaching the surface at the side.

B, Temporal bone.

C, Occipital bone.

D, Parietal bone.

E, Frontal bone.

M, Meatus auditorius externus, or external opening of the ear.

P, Mastoid process of the temporal bone, which serves to give attachment to the sterno-mastoid muscle.

SS3, Sutures, or serrated edges by which the different bones are joined together.

PLATE IV.-BASE OP THE BRAIN.

AC 1 Are the right and left hemispheres of the brain.

FF, The cerebellum

AA, The anterior lobe.

e e, The line which denotes the separation between the anterior lobe and the

middle lobe. BB, The middle lobe. CC, The posterior lobe. GrG, The Pans Varolii, which brings the two sides of the cerebellum into

communication. HH, The Medulla oblongata. r r, The Corpora pyramidalia. 5 s, The Corpora ollvaria-t t, The Corpora restiformia.

1. Olfactory nerves or first pair. Their origin is not yet demonstrated. They go through the holes in the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone, and are distributed on the membrane which lines the nostrils.

2. The optic nerves. They pass along the side of the thalami nervorwm opticorwn, and can be traced to the nates of the corpora quadriyemina, which bear a proportion to them. This is the second pair of the anatomist. They pass through the optic holes of the sphenoid bone to the orbits.

1 The following descriptions are not given by Dr Fossati. They are drawn from Dr Spurzheim's Anatomy of the Brain, aud Physiognomical System. There are some errors in Dr Fossati's work in the lettering of the plates in reference to his text, which are rectified in this publication.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PLATES. 141

3. Third pair or motores omit. They originate from the crura of the cerebrum a little before the tuber annulare. They go through the fissure between the sphenoid bone and orbitar plate of the frontal bone to the muscles of the eye-ball.

4. Fourth pair of pathetic nerves. They originate near the corpora quadri-gemina, and pass between the middle lobes of the brain and the adjacent part of the tuber annulare. They go through the same fissure as the above to the obliquus-superior muscle of the eye-ball.

5. Fifth pair of nerves, trigeminus or trifacial nerves. They may be traced to above the corpora olivaria, and go to the orbits, great part of the face, and superior and inferior maxillo.

6. Abductor nerve or sixth pair. They originate from a furrow between the posterior edge of the tuber annulare and the corpora pyramidalia. They go through the cavernous sinus and sphenoido-orbitar fissure to the abductor muscle of the eye-ball.

7. Facial nerve or portio dura, or sympatheticus minor, is the second branch of the seventh pair. They pass through the aqueduct of Fallopius, to the external ear, neck, and face, and originate at the angle formed between the Pons Varolii and the corpus restiforme.

8. Auditory nerve, or portio mollis, first branch of the seventh pair. They go through a number of small holes within the auditory passage to all the internal parts of the ear. They come from medullary streaks on the surface of the fourth ventricle.

9. Glosso-pharyngeal nerve, principal branch of the eighth pair. They go to the styloid muscles, the tongue and the pharynx.

10. Vocal nerves, or eighth pair.1 They originate from the base of the corpora olivaria. They go to the tongue, the pharynx, larynx, and lungs, and part to the stomach.

11. Spinal accessory nerves, or spinal nerves. They originate from the beginning of the spinal marrow. They go through the condyloid hole of the occipital bone to the sterno-mastoid and trapezius muscles.

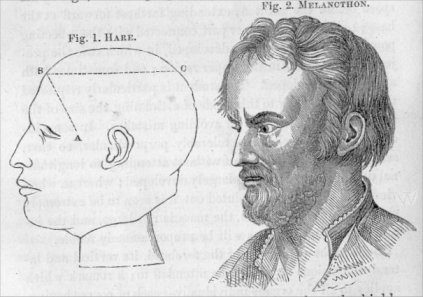

P LATE V.-THE BRAIN SEEN FROM ONE SIDE, AND PLACED AS IT IS IN THE SKULL.

The numbers refer to the organs as marked on the Plate at the beginning of the Book. The letters have the following references. A, Anterior lobe of the Brain.

B, Organ of Taetility, described by Dr Fossati under the organ of Weight. a, Alimentiveness. C, Posterior lobe of the Brain.

G, Pons Varolii which brings the two sides of the cerebellum into communication.

H, The medulla oblongata. F, The Cerebellum.

PLATE VI.-THE BRAIN SEEN AT ITS BASE, AND DISSECTED SO AS TO SHEW THE DIRECTION OF ITS FIBRES.

The letters

refer to the same parts as in the description of Plate IV

adding the following : '

a, The corpus dentatum, or ganglion of the cerebellum. h, The corpus striatum.

1 In what Dr Fossati calls the vocal nerves, are included the lingual and pneumogatric.

( 142 )

PRACTICAL APPLICATION OF THE PRINCIPLES OF PHRENOLOGY.

It has already been mentioned, that there are two hemispheres of the brain, corresponding in form and functions. There are therefore two organs for each mental power, one in each hemisphere. Each organ, including its supposed apparatus of communication, extends from the medulla oblongata, or top of the spinal marrow, to the surface of the brain or cerebellum ; and every person not an idiot has all the organs in a greater or less degree. Such of the organs as are situated immediately on the sides of the middle line separating the hemispheres, are included in one space on the busts and plates. To avoid circumlocution, the expression " organ" of a faculty will be used, but both organs will be thereby meant.

The brain, as formerly stated (p. 119), is not divided by lines corresponding to those delineated on the busts ; but the forms produced on the skull by its different parts when extremely large or small, resemble those there represented -though it is not be understood that the angles of the compartments are ever seen on the head.1 Each part is inferred to be a separate organ, because its size, caeteris paribus, bears a regular proportion to the energy of a particular mental faculty.

As size, caeteris paribus, is a measure of power,2 the first object ought to be to distinguish the size of the brain generally, so as to judge whether it be large enough to admit of manifestations of ordinary vigour ; for, as we have already seen (p. 43), if it be too small, idiocy is the invariable consequence. The second object should be to ascertain the relative proportions of the different parts, so as to determine the direction in which the power is greatest.

1 In Dr Gall's plates, the organs are, in many instances, represented apart from each other, and all of them bounded entirely by curved lines, without angles. See his Atlas, Plates 98, 99, 100.

2 See Introduction, p. 34, et seq.

APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

It is proper to begin with observation of the more palpable differences in size, and particularly to attend to the relative proportions of the different lobes. The size of the anterior lobe is the measure of intellect. It lies on the super-orbitar plates, and a line drawn along their posterior margin, across the head, will be found to terminate, externally, at that point (A in fig. 1) where the parietal bone, the frontal bone, the ethmoidal bone, and the temporal bone approach nearest to each other. If the skull be placed with the axis of the eyes parallel with the horizon, and a perpendicular be raised from the most prominent part of the zygomatic arch, it will be found to intersect the point before described. In the living head, the most prominent part of the zygomatic arch may be felt by the hand. The anterior lobe lies before the point first described, and before and below Benevolence. Sometimes the lower part of the frontal lobe, connected with the perceptive faculties, is the largest, and this is indicated by the space before the point A, extending farthest forward at the base ; sometimes the upper part, connected with the reflecting powers, is the most amply developed, in which case the projection is greatest in the upper region ; and sometimes both are equally developed. The student is particularly requested to resort invariably to this mode of estimating the size of the anterior lobe, as the best for avoiding mistakes. In some individuals, the forehead is tolerably perpendicular, so that, seen in front, and judged of without attending to longitudinal depth, it appears to be largely developed ; whereas, when viewed in the way now pointed out, it is seen to be extremely shallow. In other words, the mass is not large, and the intellectual manifestations will be proportionately feeble.

Besides the projection of the forehead, its vertical and lateral dimensions require to be attended to ; a remark which applies to all the organs individually-each of course having, like other objects, the three dimensions of length, breadth, and thickness.

144 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

The posterior lobe is devoted chiefly to the animal propensities. In the brain its size is easily distinguished ; and in the living head a perpendicular line may be drawn through the mastoid process, and all behind will belong to the posterior lobe. "Wherever this and the basilar region are large, the animal feelings will be strong ; and vice versa.

The coronal region of the brain is the seat of the moral sentiments ; and its size may be estimated by the extent of elevation and expansion of the head above the organs of Causality in the forehead, and of Cautiousness in the middle of the parietal bones. When the whole region of the brain rising above these organs is shallow and narrow, the moral feelings will be weakly manifested ; when high and expanded, they will be vigorously displayed.

Fig. 1. represents the head of William Hare, the brutal associate of Burke in the murder of sixteen individuals in Edinburgh, for the purpose of selling their bodies for dis-

section.1 Fig. 2. represents that of Melancthon, the highly intellectual, moral, religious, and accomplished associate of

1 See Phrenological Journal, v. 549.

APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES. *141

Luther in effecting the Reformation in Germany.1 All that lies before the line AB, in fig. 1, is the anterior lobe, comprising the organs of the intellectual faculties. The space above the horizontal line BC, marks the region of the moral sentiments. The space from A backwards, below B C, indicates the region of the propensities.

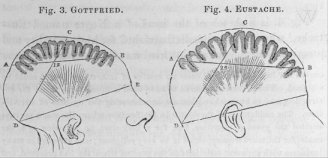

Fig. 3. represents the head of Gesche Margarethe Gottfried, a cruel and treacherous female, who was executed at Bremen in 1828, for poisoning, in cold blood, during a succession of years, both her parents, her three children, her first and second husbands, and about six other individuals.2

1 Spurzheim's Phrenology in Connection with the Study of Physiognomy. p. 160.

2 This woman's history will be found in The Phrenological Journal, vol. vii. p. 560, Such cases are not unknown in other countries, and it appears to me that much suffering might be avoided were the physiology of the brain attended to on the first indications of Destructiveness. In the " Daily News" of 20th December 1851, the following trial is reported :-" One of the most extraordinary cases ever brought before a criminal court has just been tried by the Court of Assizes of the Ille-et-Vilaine. The prisoner was a female named Hélène Jagado, who for several years past has been a servant in different families of the department. She stood at the bar charged with several thefts committed in and since the year 1846, and with seven murders by arsenic in 1850 ; but the evidence shewed that although only seven eases had been selected, as more recent, and therefore more easy of proof not less than 43 persons had been poisoned by her with arsenic. The victims were either her masters or mistresses, or fellow-servants, who had in-

I

'142 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

The line AB commences at the organ of Causality B, and passes through the middle of Cautiousness 12. These points are in general sufficiently distinguishable on the skull, and the line can easily be traced. The convolutions lying above the line AB must have been shallow and small, compared with those below, which are devoted to the animal propensities.

Fig. 4. is a sketch of the head of a Negro named Eus-tache,1 who was as much distinguished for high morality and practical benevolence as Gottfried was for deficiency of these

curred her hatred. In some cases no motive of interest or hatred could be assigned. The prisoner appeared to have been actuated by a thirst for destruction, and to have taken pleasure in witnessing the agonies of her victims. The suddenness of the deaths in the families where she was a servant excited the greatest sensation, but, for a long time, no suspicion as to the cause, for the murderess appeared to be very religious ; she attended in many instances with apparent solicitude on the persons whom she had poisoned, and so successful was her hypocrisy that even the deaths of the mother and another relative of a physician in whose family she lived raised no suspicion of poison in his mind. The prisoner herself frequently exclaimed, after the death of a victim, " How unhappy I am ; wherever I go, death follows me." The cases on which she was brought to trial were established by the evidence beyond the possibility of doubt. The prisoner, throughout the trial, which lasted ten days, constantly declared that she was innocent ; and seemed to anticipate an acquittal on account of there being no proof of her having had arsenic in her possession. It was proved, however, that in one of the families in which she was a servant, some years ago, there was a large quantity of arsenic which was not locked up, and that it had suddenly disappeared. This arsenic had, without doubt, served for the commission of the successive murders. The only defence set up for her was founded on phrenological principles. It was contended that the organs of hypocrisy (Secretiveness) and Destructiveness were developed to a degree which overpowered the moral faculties, and that, although it would be unsafe to leave her at large, she ought not to be condemned to capital punishment, the peculiarity of her organization rendering her rather an object of pity. This defence failed entirely ; and, the jury having delivered a verdict without extenuating circumstances, the court condemned her to death." There is presumptive evidence in these facts themselves that the defence was well founded, for on no other hypothesis could such conduct be accounted for. No description is given of her brain. 3 Phrenological Journal, vol. ix. p. 134. See also the section on Benevolence in this work.

APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES. *143

qualities. During the massacre of the whites by the Negroes in St Domingo, Eustache, while in the capacity of a slave, saved, by his address, courage, arid devotion, the lives of his master, and upwards of 400 other whites, at the daily risk of his own safety. The line AB is drawn from Causality, B, through Cautiousness, 12 ; and the great size of the convolutions of the moral sentiments may be estimated from the space lying between that line and the top of the head C.

Both of the sketches are taken from busts, and the convolutions are drawn suppositively for the sake of illustration. The depth of the convolutions, in both cuts, is greater than in nature, that the contrast may be rendered the more perceptible. It will be kept in mind that I am here merely teaching rules for observing heads, and not proving particular facts. The spaces, however, between the line AB and the top of the head are accurately drawn to a scale. Dr Abram Cox has suggested, that the size of the convolutions which constitute the organs of Self-Esteem, Love of Approbation, Concentrativeness, Adhesiveness, and Philoprogenitiveness, may be estimated by their projection beyond a base formed by a plane passing through the centres of the two organs of Cautiousness and the spinous process of the occipital bone. He was led to this conclusion by a minute examination of a great number of the skulls in the collection of the Phrenological Society. A section of this plane is represented by the lines CD, in figs. 3 and 4.

To determine the size of the convolutions lying in the lateral regions of the head, Dr Cox proposes to imagine two vertical planes passing through the organs of Causality in each hemisphere, and directly backwards, till each meets the outer border of the point of insertion of the trapezius muscle at the back of the neck. The more the lateral convolutions project beyond these planes, the larger do the organs in the sides of the head appear to be-namely, Combativeness, Destructiveness, Secretiveness, Cautiousness, Acquisitiveness.

144 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

and Constructiveness ; also to some extent Tune, Ideality. Wit, and Number.

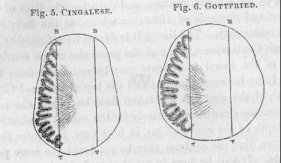

Fig. 5. represents a horizontal section of the skull of a Cingalese, the lines B T being sections of the planes above described. Fig. 6. represents the same section of the skull of Gottfried, the female poisoner already referred to. The lateral expansion of the head beyond the lines B T in fig. 6, forms a striking contrast with the size of the same regions in fig. 5. The Cingalese are a tribe in Ceylon, and in disposition are remarkably mild and pacific.1

Dr Cox suggests farther, that the size of the convolutions lying at the base of the brain, may be estimated by their projection below a plane passing through the superciliary ridges and the occipital spine (D E, fig. 3, and D, fig. 4), and by observing the distance at which the opening of the ear. the mastoid process, and other points of the base of the skull, lie below that plane.

So many instances have occurred in which I have verified the accuracy of the inferences drawn from the projection of the brain beyond these planes, that I recommend this mode of observation as useful in practice. In the course of my lectures, I have frequently pointed out the difference, in different individuals, in the position of the opening of the ear in relation to the level of the eye, as one

1 See description of their character in The Phrenological Journal, vii. 634.

REGIONS OF THE BRAIN. 145

indication of the size of the organ of Destructiveness, and of the basilar convolutions situated inward from it towards the mesial plane. The lower the ear descends, the larger are the inferior convolutions of the middle lobe, which occupy the middle fossae of the skull. Individuals in whom the opening of the ear stands nearly on a level with the eye, are in general little prone to violence of temper. Dr G. M. Paterson mentions incidentally, in his paper " On the Phrenology of Hindustan,"1 that the situation of the ears is high in the Hindoos, while, at the same time, their skulls, over the organ of Destructiveness, are " either quite flat, or indicate a slight degree of concavity."

I have multiplied observations to so great an extent in regard to the above-described methods of estimating the size of the anterior lobe and the coronal region of the brain, that I regard them as altogether worthy of reliance. The observations on the planes suggested by Dr Abram Cox, however, are still too limited to authorize me to state these as certain guides. They are open to the verification of every observer. I particularly recommend to students of Phrenology who have opportunities of dissecting the brains of individuals whose dispositions are known, to run straight wires through the brain before removing it from the skull, in the directions of the lines represented in the figures ; then to make sections, passing through the course of the wires ; and to observe and report to what extent the convolutions develope themselves externally from the planes so formed.

By observing the proportions of the different regions, it will be discovered, that in some instances the anterior lobe bears a large and in others a small proportion to the rest of the head ; in some cases the coronal region is large in proportion to the base, while in others it is small. The busts of the Reverend Mr M., Pallet, Steventon, and Sir Edward Parry, may be contrasted with this view.2 Great differences also

1 Transactions of the Phrenological Society (Edin. 1824) p 443

" The casts and skulls referred to in this and subsequent pages, as illustrative of particular organs, are to be found in the collection of the' Phreno-

K

146 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

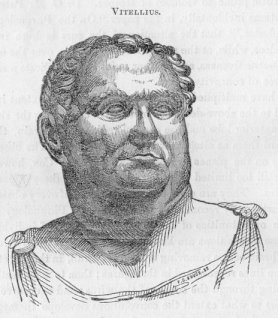

in projection beyond the line running from Causality to the trapezius, will be discovered. A head that is very broad in proportion to its height, indicates a mind in which the lower propensities are the ruling springs of action. The Roman emperor Vitellius, a monster of vice, is represented with such a head.

After becoming familiar with the general size and configuration of heads, the student may proceed to the observation of individual organs : in studying them, the real dimensions, including length, breadth, and thickness, and not merely the prominence of each organ, should be looked for.

The length of an organ, including its supposed apparatus of communication, is ascertained by the distance from the

logical Society. Duplicates of most of them are exhibited and sold by Mr James Deville, Strand, London ; by Mr Anthony O'Neil, Edinburgh ; and by their agents.

LENGTH AND BREADTH OF ORGANS. 147

medulla oblongata to the peripheral surface. A line passing through the head from one ear to the other, would nearly touch the medulla oblongata, and hence the external opening of the ear is assumed as a convenient point from which to estimate length. The breadth of an organ is judged of by its peripheral expansion ; for it is a general law of physiology, that the breadth of an organ throughout its whole course bears a relation to its expansion at the surface ; the optic and olfactory nerves are examples in point.

It has been objected that the breadth of the organs cannot be ascertained, because the boundaries of them are not sufficiently determinate. In answer I observe, that although the boundaries of the different organs cannot be determined with mathematical precision, like those of a triangle, a square, or a rhomboid, yet, in a single case, an accurate observer may make a very near approximation to the truth ; and, in a great multitude of cases, the very doctrine of chances, and of the compensation of errors, must satisfy any one that these boundaries may be defined with sufficient precision for all practical purposes. Even in the exact sciences themselves, an approximate solution is frequently all that is attainable ; and if the opponents would only make themselves masters of the binomial theorem, or pay a little attention to the expansion of infinite series, they would not persist in calling for a degree of accuracy which is impossible, or in neglecting an important element in a calculation, because it is involved in a certain liability to error within very narrow limits. The absurdity of the reason assigned for this omission, is rendered still more apparent by the case of the prismatic spectrum, which I conceive to be exactly in point. Now, what is it that this beautiful phenomenon displays ? The seven primary colours, arranged in a peculiar order, and glowing with an almost painful intensity. But each of these colours occupies a certain space in relation to the whole, the boundaries of which it may be impossible for the hand or eye to trace with geometrical precision, although the relative space in question

148 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

has nevertheless been made the subject of measurement, and a very close approximation obtained from the mean of a vast number of trials. According to the principle followed by some antiphrenologists, however, breadth should be altogether neglected, on the ground that the boundaries of the respective colours are " purely ideal ;" as if a mathematical line were not the most perfect idealism or abstraction which the mind of man can possibly form. This idealism, or abstraction, however, has no more to do with those approximations which-may be obtained practically by repeated trials, than the mathematical definition of a line with a metallic rod ; and it is a mere quibble to pretend, for example, that we ought not to measure the length of the rod, because it may not correspond with the definition of the line. Upon the strange principle which some opponents have adopted, they must be prepared to maintain, that the boundaries of a hill or hillock are purely ideal, and depend in every instance on the fancy of the measurer.1 After the nerves of sensation and motion have combined at F. (figure, p. 91) it is no longer possible to distinguish them by their appearances, yet it is generally admitted that they continue distinct in. their whole course. Another illustration is afforded by geology. The leading rocks bear so many characteristic marks of distinction, that no ordinary observer can mistake them ; yet particular specimens graduate so much into each other, that the most skilful observers will sometimes err, and believe basalt to be claystone, or gneiss to be granite. In teaching this science, however, the leading features of the rocks are found sufficient to guide the student to knowledge of the principles, and his own sagacity, improved by experience, enables him in due time to deal successfully with the intricacies and difficulties of the study. The same rule ought to be followed in cultivating Phrenology.2

The whole organs in a head should be examined, and their

1 Caledonian Mercury, llth June 1829.

" See additional illustrations in The Phrenological Journal, viii. 640.

PHRENOLOGICAL BUST, *149

relative proportions noted.1 Errors may be committed at first; but without practice, there will be no expertness. Practice, with at least an average endowment of the organs of Form, Size, Individuality, and Locality, are necessary to qualify a person to make observations with success : individuals whose heads are very narrow between the eyes, and little developed at the top of the nose, where these organs are placed, experience great difficulty in distinguishing the situations and minute shades in the proportions of different organs. If one organ be much developed, and the neighbouring organs very little, the developed organ will present an elevation or protuberance ; but if the neighbouring organs be developed in proportion, no protuberance can be perceived, and the surface is smooth. The student should learn from books, plates, and casts, or personal instruction (and the last is by far the best), to distinguish the form of each organ, and its appearance when developed in different proportions to the others, because there are slight modifications in the position of them in each head.

The phrenological bust shews the situations of the organs,

1 " There are many convolutions," says Dr Spurzheim, " in the middle line between the two hemispheres of the brain, and others at the basis and between the anterior and middle lobes, which do not appear on the surface ; but it seems to me that a great part, at least, of every organ does present itself there, and further, that all the parts of each organ are equally developed, so that, though a portion only appear, the state of the whole may be inferred. The whole cerebellum reaches not the skull, yet its function may be determined from the part which does. The cerebral parts situated in the middle line between the hemispheres, seem proportionate to the superincumbent convolutions ; at least I have always observed a proportion, in the vertical direction, between them." -Phrenology, p. 116.

" The cerebral parts situated around and behind the orbit, also require some care and experience on the part of the phrenologist, to be judged of accurately. Their development is discoverable from the position of the eyeball, and from the figure of the superciliary ridge. According as the eye-ball is prominent or hidden in the orbit, depressed or pushed sideward, inward, or outward, we may judge of the development of the organs situated around and behind it."-Ibid. Particular directions for observing the parts there situated will be given, when treating of the individual organs.

150 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

and their proportions, only in one head ; and it is impossible by it to communicate more information.1 The different ap-

1 Attempts have been made by opponents to represent certain changes in the numbering and marking of the organs in busts recently published, as " a Revolution in Phrenology." A brief explanation will place this matter in its true light. The phrenological bust sold in the shops is an artificial head, the utility of which depends on the degree in which the delineation of the organs on it approaches to the appearances most generally presented by the organs in nature. The first bust sold in this country exhibited the organs as they would be found in a particular head not very common in this country, the bust having been imported from the Continent, and national heads being modified as much as national features. On the 1st of October 1824, a new bust was published in Edinburgh, in which the delineation exhibited more accurately the appearances and relative proportions of the organs in this country. Subsequent observations shewed that this bust might be brought still more closely to resemble the most common proportions of the organs in Britain ; and, on the 1st of April 1829, certain modifications were made on it accordingly. The head selected is very nearly of the full average size. It was selected because the three orders of organs, those of the Propensities, Sentiments, and Intellectual Faculties were all well developed. In mapping out the different organs a great number of skulls and casts of the head were consulted, and the forms and situations of the organs in them were copied, as far as possible. For example, the organ of Amativeness was delineated after its form in a skull in which it was strongly marked. Philoprogenitiveness was copied from the skull marked No. 2. Plate LX. in the Atlas which accompanies Dr Gall's large work, of which we possess a cast, and in which it stands forth as distinctly as the nose on the human face. Concentrativeness was drawn from a cast of the head of a gentleman in whom it was very large, aided by another cast in which it was very small. Adhesiveness is delineated chiefly from negative instances, that is to say, from skulls and casts in which it is depressed ; David Haggart's, for example, is one. In many skulls and casts, such as the Swiss skulls, the cast of the head of Mrs H., &c., the organ is largely developed; but it does not stand forth in a definite form, on account of the neighbouring organs being also large. In the negative cases there is a depression corresponding to that single organ ; and its situation, therefore, with an approximation to its form, was to be found by reference to them. Combativeness stands forth in a distinct form in the skull of General Wurmser, of which we have a cast. Destructiveness is equally conspicuous in the skull of Bellingham. Secretiveness stands singly prominent in a Hindoo skull which we possess ; it is also predominant in the skull marked " a Cunning Debtor," in Gall's collection. Acquisitiveness stands forth as a predominant single organ in a skull in the Phrenological Society's collection here, and on the faith of its form and position in this head, we

PHRENOLOGICAL BUST. 151

pearances in all the varieties of relative size, must be discovered by inspecting a number of heads ; and especially by

declined to adopt a new marking of this organ introduced by Dr Spurzheim from anatomical considerations alone. The accuracy of our marking has been borne out by many subsequent examples. Constructiveness may be seen as a single round organ in the cast of the skull formerly ascribed to Raphael, and in that of the " Milliner of Vienna ;" and it is also very distinctly marked in several of the " Greek" skulls. Self-Esteem stands prominent in the cast of a head in our museum, and it is singly deficient in the skulls of Dr Hette, an " American Indian," and several others. Love of Approbation presents its peculiar form in the " American Indian," the " Peruvian," and many others. We have the organ of Cautiousness standing forth in its distinctive form in the " Tom-tom boy," and in at least a dozen of other skulls in the Society's collection. Benevolence is clearly defined in the mask of Jacob Jervis. Veneration stands as a predominating organ in the skull of an old woman in Dr Gall's collection, of which we have a cast ; and it is singly deficient in forty or fifty skulls in our possession. Hope is large, and Veneration deficient, in an " open skull " which I use in my lectures : we have no good specimen of its standing forth as a single prominent organ ; but we have many of its single deficiency, presenting a depression of a recognisable form in a specific locality. Firmness stands forth in the casts of D. Haggart, King Robert Bruce, and in many others ; while it forms a complete hollow in the head of Mrs H. Conscientiousness is perfectly defined in the head of Mrs II., while it is remarkably deficient in the skulls of Bruce and Haggart. Ideality is found well marked in some of the " Greek skulls," and in the poets and artists, while it is extremely deficient in Haggart and the criminals in general. The same mode of fixing the situations and forms of all the other organs was followed, and above all, the anatomy of the skull was constantly kept in view in the delineations. By consulting the casts mentioned under each of the organs, in the subsequent pages of this work, additional authorities will be found for the forms and situations assigned to the greater part of the organs in the artificial bust. The nature of the changes made on this bust may be explained by a simple illustration. Suppose that, in 1819, a-a artist" had model] ed a bust, resembling, as closely as his skill could reach, the face most commonly met with in Scotland, and that, to save the trouble of referring to the different features by name, he had attached numbers to them, beginning at the chin, and calling it No. 1, and so on up to the brow' which we may suppose to be No. 33-^-in this bust he would necessarily give certain proportions to the eyes, nose, cheek, mouth, and chin. But suppose he were to continue his observations for five years, it is quite conceivable he might come to be of opinion that, by making the nose a little shorter, the mouth a little wider, the cheeks a little broader, and the chin a little sharper, he could bring the artificial face nearer to

152 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

contrasting instances of extreme development with others of extreme deficiency. No adequate idea of the foundation of the science can be formed until this is done. In cases of extreme size of single organs, a close approximation to the form delineated 011 the bust (leaving angles out of view) is distinctly perceived.

The question will perhaps occur-If the relative proportions of the organs differ in each individual, and if the phrenological bust represents only their most common proportions, how are their- boundaries to be distinguished in any particular living head 1 The answer is, By their forms and appearances. Each organ has a form, appearance, and situation, which it is possible, by practice, to distinguish in the living head, otherwise Phrenology cannot have any foundation.

When one organ is very largely developed, it encroaches

the most general form of the Scottish countenance ; and that he might arrange the numbers of the features with greater philosophical accuracy : and suppose he were to publish a new edition of his bust with these modifications of the features, and with the numeration changed so that the mouth should be No. 1, the chin No. 5, and the brow No. 35, what should we think of a critic who should announce these alterations as " a revolution" in human physiognomy, and assert that, because the numbers were changed, the nose had obliterated the eyes, and the chin had extinguished the mouth Î This is what the opponents have done in regard to the new phrenological bust. In the modifications which have been made on it, the essential forms and relative situations of all the organs have been preserved, and there is no instance of the organ of Benevolence being turned into that of Veneration, or Veneration into Hope, any more than, in the supposed new modelled face, the nose would be converted into the eyes, or the eyes into the mouth.

In regard to the numeration, again, the changes are exactly analogous to those which are before supposed to take place in regard to the features. The organ of Ideality formerly was numbered 1G, and now it is numbered 19 ; but the organ and function are nothing different on this account. Dr Spurzheim adopted a new order of numbering, from enlarged observation of the anatomical relations of the organs, and his improvements have been adopted in Edinburgh and Dublin. He, however, in the United States of America, again altered the forms and numbering of several of the organs. I have never been able to discover sufficient evidence in nature to authorize these last changes, and I have not adopted them. See, farther, with respect to the marked bust, The Phrenological Journal, xii. 362.

APPEARANCES OF ORGANS. 153

on the space usually occupied by the neighbouring organs, the situations of which are thereby slightly altered. When this occurs, it may be distinguished by the greatest prominence being near the centre of the large organ, and the swelling extending over a portion only of the others. In these cases the shape should be attended to ; for the form of the organ is then easily recognised, and is a sure indication of the particular one which is largely developed.

The observer should learn, by inspecting a skull, to distinguish the mastoid process behind the ear, as also certain bony excrescences sometimes formed by the sutures, and several bony prominences which occur in every head,-from elevations produced by development of brain.

In observing the appearance of individual organs, it is proper to begin with the largest, and select extreme cases. The mask of Mr Joseph Hume may be contrasted with that of Dr Chalmers for Ideality ; the organ being much larger in the latter than in the former. The casts of the skulls of Burns and Haggart may be compared at the same part ; the difference being equally conspicuous. The cast of the Reverend Mr M. may be contrasted with that of Dempsey, in the region of Love of Approbation ; the former having this organ large, and the latter small. Self-Esteem in the latter, being exceedingly large, may be compared with the same organ in the skull of Dr Hette, in whom Love of Approbation is much larger than Self-Esteem. Destructiveness in Bellingham may be compared with the same organ in the skulls of the Hindoos ; the latter people being in general tender of life. Firmness large, and Conscientiousness deficient, in King Robert Bruce, may be compared with the same organs reversed in the cast of the head of a lady (Mrs H), which is sold as illustrative of these organs. The object of making these contrasts is to obtain an idea of the different appearances presented by organs, when very large and very small.

The terms used by the Edinburgh phrenologists to denote

154 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

the gradations of size in the different organs, in an increasing ratio, are

Very small. Moderato. Rather large.

Small. Rather full. Large.

Bather small. Full. Very large.

Sir John Ross has suggested, that numerals may be applied with advantage to the notation of development. He uses decimals ; but these appear unnecessarily minute. The end in view may be attained by such a scale as the following :

1. 8. Rather small. 15.

2. Idiocy. 9. 16. Rather large.

3. 10. Moderate. 17.

4. Very small, 11. 18. Large.

5. 12. Rather full. 19.

6. Small. 13. 20. Very largo.

7. 14. Full.

The intermediate figures denote intermediate degrees of size, for which we have no names. The advantage of adopting numerals is, that the values of the extremes being known, we can judge accurately of the dimensions denoted by the intermediate numbers ; whereas it is difficult to apprehend precisely the degrees of magnitude indicated by the terms small, full, large, &c., unless we have seen them applied by the individual who uses them. These divisions have been objected to as too minute ; but by those who have long practised Phrenology, this is not found to be the case. It has even been said that it is impossible to distinguish the existence of several of the organs in consequence of their minute size. This objection is obviously ill-founded. A lady finds it quite possible to distinguish the head from the point of a pin, and to discover the eye of a needle. Artizans can not only perceive the links in the chain attached to the mainspring of a watch, but are able to fabricate them ; engravers distinguish the minutest lines which they employ to produce shade in pictures ; and printers not only discriminate at a glance the smallest types used in their art. but distinguish

POWER OF DISCRIMINATION. 155

between a period and a comma ; compared with which objects the smallest phrenological organ is of gigantic size. There is, however, difficulty in distinguishing the size and relative proportions of the minuter organs. But practice has an astonishing effect in giving acuteness to the perception of differences in the appearance of these as well as of other objects. A schoolboy or labourer will confound manuscripts of different aspects, while an experienced copyist finds no difficulty in ascribing each of a hundred pages, written by as many individuals, to its appropriate penman. When there is a question of forgery in a court of law. the judge remits to an engraver to report whether or not the signature is genuine, because it is known that the familiarity of engravers with the minute forms of written characters enables them to discriminate points of identity and difference which would escape the notice of ordinary observers. How frequently, moreover, do strangers mistake one member of a family for another, although the real difference of features is so obvious to the remaining brothers and sisters that they are puzzled to discover any resemblance whatever ! How easily does the experienced physician distinguish two diseases, by the similarity of whose symptoms a novice would be at once misled ! And with what facility does a skilful painter discriminate a copy from an original! It was only after a continued and attentive study of Raphael's pictures that Sir Joshua Reynolds was able to perceive their excellencies. " Nor does painting," he adds, " in this respect differ from other arts. A just poetical taste, and the acquisition of a nice discriminative musical ear, are equally the work of time. Even the eye, however perfect in itself, is often unable to distinguish between the brilliancy of two diamonds : the experienced jeweller will be amazed at this blindness, though his own powers of discrimination were acquired by slow and scarcely perceptible degrees." So it is with Phrenology. The student is often at first unable to perceive differences which, after a few months, become palpably manifest to him, and at the former obscurity of which

156 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

he is not a little surprised. The following anecdote, related by Dr Gall,1 is in point. The physician of the House of Correction at Graetz in Stiria, sent him a box filled with skulls. In unpacking them, he was so much struck with the extreme breadth of one of them at the anterior region of the temples, that he exclaimed, " Mon Dieu, quel crâne de voleur!" Yet the physician had been unable to discover the organ of Acquisitiveness in that skull. His letter to Dr Gall, sent with the box, was found to contain this information : " The skull marked ---is that of N---, an incorrigible thief."

With respect to the practical employment of the scale above described, it is proper to remark, that as each phrenologist attaches to the terms small, moderate, full, Sec., shades of meaning perfectly known only to himself and those accustomed to observe heads along with him, the separate statements of the development of a particular head by two phrenologists, are not likely to correspond entirely with each other. It ought to be kept in mind, also, that these terms indicate only the relative proportions of the organs to each other in the same head ; but as the different organs may bear the same proportions in a small and in a large head, the terms mentioned do not enable the reader to discover, whether the head treated of be in its general magnitude small, moderate, or large. To supply this information, measurement by callipers is resorted to; but this is used not to indicate the dimensions of particular organs, for which purpose it is not adapted, but merely to designate the general size of the head.

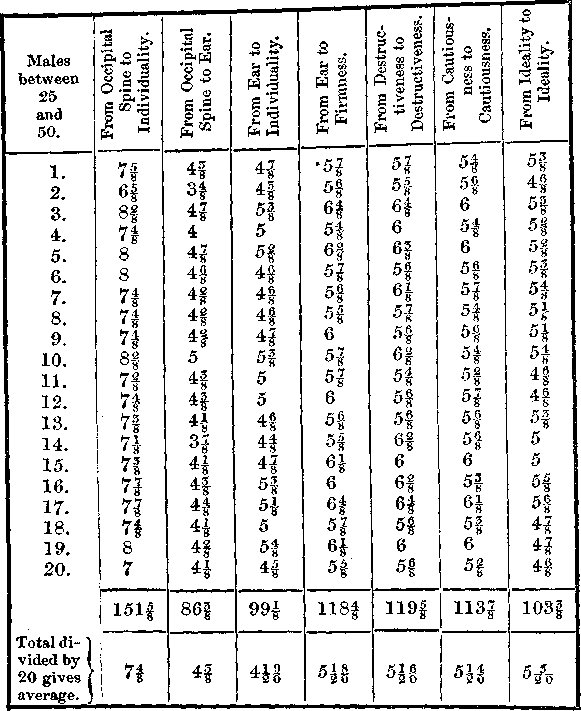

The following are a few measurements from nature, taken promiscuously from many more in my possession.2

1 Sur les Fonctions du Cerveau, iv. 240.

4 The most successful efforts in the measurement of skulls with which I am acquainted, are those made by Mr Phillips and Dr Morton of Philadelphia, and recorded in the excellent work by the latter, entitled Crania Americana (Philadelphia, 1839). 1 saw the method-practised when that work was in preparation, and can recommend it as

These measurements are taken above the integuments, and shew the sizes of the different heads in the directions specified ; but I repeat that they are not given as indicative of the dimensions of any particular organs. The callipers

the best yet applied to the attainment of the object in view. Dr Morton's work is exceedingly interesting to phrenologists, and very ably executed. Notices of it will be found in The Phrenological Journal xiii. 351, 303.

158 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

are not suited for giving this latter information ; for they do not measure length from the medulla oblongata, or projection beyond the planes mentioned above ; neither do they indicate breadth : all of which dimensions must be attended to, in estimating the size of individual organs. The average of these twenty heads is probably higher than that of the natives of Britain generally, because there are several large heads among them, and none small.

It ought to be kept constantly in view, in the practical application of Phrenology, that it is the size of each organ in proportion to the others in the head of the individual observed, and not their absolute size, or their size in reference to any standard head, that determines the predominance in him of particular talents or dispositions.1 Thus, in the head of Bellingham, Destructiveness is very large, and the organs of the moral sentiments and intellect are small in proportion ; and according to the rule, that, caeteris paribus, size is the measure of power, Bellingham's strongest tendencies are inferred to have been towards cruelty and rage. In several Hindoo skulls in the Phrenological Society's collection, the organ of Destructiveness is small in proportion to the others, and we conclude that the tendency of such individuals would be weakest towards the foregoing passions. But in the head of Gordon, the murderer of a pedlar boy, the absolute size of Destructiveness is less than in the head of Dr Spurzheim ; yet Dr S. was an amiable philosopher, and Gordon an atrocious murderer. This illustrates the rule, that we ought not to judge by absolute size. In Gordon, the organs of the moral sentiments and intellectual faculties are small in proportion to that of Destructiveness, which is the largest in the brain ; while in Spurzheim, the moral and intellectual organs are large in proportion to Destructiveness. On the foregoing principles, the most powerful manifestations of Spurzheim's mind ought to have been in the department of sentiment and intellect, and those of Gordon's mind in Destructiveness and other

1 See Phren, Journal. viii. 642.

ABSOLUTE SIZE NO CRITERION. 159

animal passions ; and their actual dispositions corresponded. Still the dispositions of Spurzheim were affected by the large size of this organ. It communicated & warmth and vehemence of temper, which are found only when it is large, although the higher powers restrained it from abuse. Dr Spurzheim said to me : " Ï am too angry to answer that attack just now ; I shall wait six months ;"-and he did so, and then wrote calmly like a philosopher.

It is one object to prove Phrenology to be true, and another to teach a beginner how to observe organs. For the first purpose, we do not in general compare an organ in one head with the same organ in another ; because it is the predominance of particular organs in the same head that gives ascendancy to particular faculties in the individual, and therefore, in proving Phrenology, we visually compare the different organs of the same head. But in learning to observe, it is useful to contrast the same organ in different heads, in order to become familiar with its appearance in different sizes and combinations.

With this view, it is proper to begin with the larger organs ; and two persons of opposite dispositions in the particular points to be compared, ought to be placed in juxtaposition, and their heads observed. Thus, if we take the organ of Cautiousness, we should examine its development in those whom we know to be remarkable for timidity, doubt, and hesitation ; and we should contrast its appearance with that which it presents in individuals remarkable for precipitancy, and into whose minds doubt or fear rarely enters. Or a person who is passionately fond of children, may be compared, in regard to the organ of Philoprogenitiveness, with another who regards them as an intolerable annoyance. No error is more to be avoided, than beginning with the observation of the smaller organs, and examining these without a contrast.

An objection is frequently stated, that persons having large heads have " little wit," while others with small heads arc " very clever." The phrenologist never compare« intellec-

160 APPLICATION 01? PRINCIPLES.

tual ability with size of the brain in general ; for a fundamental principle of the science is, that different parts of the brain have different functions, and that hence the same absolute quantity of brain, if consisting of intellectual organs, may be connected with the highest genius,-while, if consisting of the animal organs, lying in the basilar and occipital regions of the head, it may indicate the most fearful energy of the lower propensities. The brains of a savage tribe might be equal in absolute size to those of average Europeans ; yet, if the chief development of the former were in the animal organs, while the latter have a comparatively great endowment of the organs of moral sentiment and intellect, no phrenologist would expect the one people to be equal in intelligence and morality to the other, merely because their brains were equal in absolute magnitude. The proper test is to take two heads, in sound health, and similar in temperament, age, and exercise, in each of which the several organs are similar in their proportions, but the one of which is large, and the other small ; and then, if the preponderance of power of manifestation be not in favour of the first, Phrenology must be abandoned as destitute of foundation.

In comparing the brains of the lower animals with the human brain, the phrenologist looks solely for the reflected light of analogy to guide him in his researches, and never founds a direct argument in favour of the functions of the different parts of the human brain upon any facts observed in regard to the lower animals ; and the reason is, that such different genera of animals are too dissimilar in constitution and external circumstances, to authorize him to draw positive results from comparing them. " We should never," says Dr Vimont, " commence the application of the principles of Phrenology on the crania of individuals belonging to different classes and orders of animals. It should always be on the crania of animals of the same species, and especially on animals the produce of the same parents. Every one who will take the trouble to repeat my experiments, by rear-

e

BRAINS OF LOWER ANIMALS. 161

ing before his own eyes, and during a long period, a large number of animals, and noting with care their most prominent faculties, will be qualified to make valuable cranioscopical observations on the chief vertebrated animals."1 Many philosophers, being convinced that the brain is the organ of mind, and having observed that the human brain is larger than that of the majority of tame animals, as the horse, clog, and ox, have attributed the mental superiority of man to the superiority in absolute size of his brain ; but the phrenologist does not acknowledge this conclusion as in accordance with the principles of his science. The brain in one of the lower creatures may be very large, and nevertheless, if it be composed of parts appropriated to the exercise of muscular energy or the manifestation of animal propensities, its possessor may be far inferior in understanding or sagacity to another animal, having a smaller brain, but composed chiefly of parts destined to manifest intellectual power.2 "Whales and elephants have a brain larger than that of man, and yet their sagacity is not equal to his ; but nobody has shewn that the parts destined to manifest intellect are larger in these animals than in man ; and hence the superior intelligence of the human species is no departure from the general analogy of nature. I repeat, however, that it is improper to expect accurate results of any kind from a comparison of the brains of different species of animals,

In like manner, the brains of the monkey and the dog are smaller than those of the ox, hog, and ass, and yet the former approach nearer to man in regard to their intellectual faculties. To apply the principles of Phrenology to them, it would be necessary to ascertain, first, that the brain, in structure, constitution, and temperament, is precisely similar in the different species compared (which it is not) then to dis-

' Treatise on Human and Comparative Phrenology, under the head "Cranioscopy of Animals."

2 Spurzheim's Phrenology, sect. in. ch. 2. p. 54.

3 This subject is amply discussed in The Annals of Phrenology vol ii pp. 38-49; Dr Caldwell's Phrenology Vindicated (Lexington Ky 1835 pp. 62-73 ; and Tke Phrenological Journal, vol. xiv. pp. 179, 264. 389

L

162 APPLICATION OP PRINCIPLES.

cover what parts manifest intellect, and what propensity, in each species ; and, lastly, to compare the power of manifesting each faculty with the size of its appropriate organ. If size were found not to be a measure of power, then the rule under discussion would fail in that species : but even this would not authorize us to conclude that it did not hold good in regard to man ; for Human Phrenology is founded, not on analogy, but on positive observations. Some persons are pleased to affirm, that the brains of the lower animals consist of the same parts as the human brain, only on a smaller scale ; but this is highly erroneous. If the student will procure brains of the sheep, dog, fox, calf, horse, or hog, and compare them with the human brain, or with the casts of it sold in the shops, he will find a variety of parts to be wanting in the animals, especially the convolutions which form the organs of the moral sentiments and the reflecting faculties.1

In commencing the study of Phrenology, as of any science, it is of great importance to have a definite object in view. If the student desire to find the truth, he will consider first the general principles, developed in the introduction to the present work, and the presumptions for and against them, arising from admitted facts in mental philosophy and physiology. He will next proceed to make observations in nature ; qualifying himself by previous instruction in the forms, situations, appearances, and functions of the organs.

The chief circumstances which modify the effects of size, are constitution, health, and exercise ; and the student ought never to omit the consideration of these, for they are highly important. They have already been considered on pages 49-55, to which I refer. In addition to what is there stated, I observe, that the temperaments rarely occur simple in any individual, two or more being generally combined. The bilious and nervous temperament is a common combination, which gives strength and activity ; the lymphatic and nervous is also common, and produces sensitive deli-

' See Phren. Journ. ix. 514.

TEMPERAMENTS. 163

cacy of mind, conjoined with indolence. The nervous and sanguine combined give extreme vivacity, but without corresponding vigour. Dr Thomas of Paris has published a theory of the temperaments to the following effect. When the digestive organs filling the abdominal cavity are large, and the lungs and brain small, the individual is lymphatic ; he is fond of feeding, and averse to mental and muscular exertion. When the heart and lungs are large, and the brain and abdomen small, the individual is sanguine ; blood abounds and is propelled with vigour ; he is therefore fond of muscular exercise, but averse to thought. When the brain is large, and the abdominal and thoracic viscera small, great mental energy is the consequence. These proportions may be combined in great varieties, and modified results will ensue.1

When two of the temperaments are combined, one may be increased and the other diminished by exercise. Dr Spurzheim possessed the nervous and lymphatic temperament ; and I have heard him say, that his constant mental activity had increased the former and diminished the latter in his advanced years. In my courses of lectures on Phrenology, I have frequently held meetings of my classes for practical lessons on the temperaments, and have found Dr Thomas's indications strikingly supported by facts. I placed paintings of the four temperaments on the wall, and different individuals, ad libitum, came from among my audience, and stood under them. The class gave their opinions of the temperaments which were combined in each ; and I observed, as a very general result, that the brain predominated in size in those of the nervous temperament ; the lungs, in those of the sanguine ; and the abdominal viscera, in those of the lymphatic temperaments. In the nervous-lymphatic, the brain and abdominal viscera were both large. In the sanguine-

1 The views of Dr Thomas are more fully explained in The Phrenological

Journal, iv. 438, 604 ; and in Dr Caldwell's Essay on Temperament Lexington,

Kentucky, 1831. Dr Thomas's own work is entitled, Physiologie,

des Temperamens ou Constitutions, &c. Paris, 1826.

164 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

nervous, both lungs and brain were large. In one hour, I generally found that my audience could discriminate the combinations of the temperaments successfully. The ladies did themselves the great credit of standing up to have their temperaments judged of, and took an active part in the exercises.

Mr Sidney Smith1 maintains, " that the temperaments, or, in other words, the peculiar proportions in which the different elementary components of the blood are secreted in the system, are the result of the predominance of particular organs." Firmness predominant, for instance, produces the bilious temperament ; Hope predominant, the sanguine ; and Cautiousness predominant, the nervous ; while the lymphatic " is caused by the joint operation of tardy circulation and imperfect oxygenation, the result of a confined chest and feeble heart and lungs." I have not found these ideas supported by my observations.

In some individuals the brain seems to be of a finer texture than in others ; and there is then a delicacy and fineness of manifestation, which is one ingredient in genius. A harmonious combination of organs gives justness and soundness of perception, but there is a quality of fineness distinguishable from this. Byron possessed this quality in a high degree.2

If, in each of two individuals, the organs of propensity, sentiment, and intellect, are equally balanced, the general conduct of one may be vicious, and that of another moral and religious. In such a case it will be found that the circumstances of the former have been well calculated to rouse and invigorate the animal propensities and allow the moral sentiments to lie dormant, while the circumstances of the other have been directly the reverse. The native power may be equal in the propensities and sentiments ; but the circum-

1 Principles of Phrenology, p, 60.

2 See an interesting article on the quality of the brain by Mr Noble, in The Phrenogical Journal, xii, 121.

TEMPERAMENTS. 165

stances have given an acquired ascendency to the class of feelings most strenuously cultivated.

Suppose that two individuals possess an organization exactly similar, but that one is highly educated, and the other left entirely to the impulses of nature-the former will manifest his faculties with higher energy than the latter ; and hence it is argued, that size is not in all cases a measure of power.

Here, however, the requisite of coteris paribus does not hold. An important condition is altered, and the phrenologist uniformly allows for the effects of education, before drawing positive conclusions.1 It may be supposed that, if exercise thus increases power, it is impossible to draw the line of distinction between energy derived from this cause, and that which proceeds from size of the organs ; and that hence the real effects of size can never be determined. The answer to this objection is, that education may cause the faculties to manifest themselves with the highest degree of energy which the size of the organs will permit, but that size fixes a limit which education cannot surpass. Dennis, we may presume, received some improvement from education, but it did not render him equal to Pope, much less to Shakspeare or Milton : therefore, if we take two individuals whose brains are equally healthy, but whose organs differ in size, and educate them alike, the advantages in power and attainment will be greater, in proportion to the size, in him who has the larger brain. Thus the objection ends in this,- that if we compare brains in opposite conditions, we may be led into error-which is granted ; but this is not in opposition to the doctrine, that, coteris paribus, power is in proportion to size. Finally-extreme deficiency in size produces, as we have seen, incapacity for education, as in idiots ; while extreme development, if healthy, as in Shakspeare,' Franklin, Burns, Ferguson, and Mozart, anticipates its effects, in so far that the individuals educate themselves. In saying, then, that, coteris paribus, size is a measure of

1 Trans, of the Phren. Soc. p. 308.

166 APPLICATION OF PRINCIPLES.

power, phrenologists demand no concessions which are not made to physiologists in general ; among whom, in this as in other instances, they rank themselves.

There is a great distinction between power and activity of mind; and it is important to keep this difference in view. Power, strictly speaking, is the capability of thinking, feeling, or perceiving, however small in amount that capability may be ; and in this sense it is synonymous with faculty : action is the exercise of power ; while activity denotes the quickness, great or small, with which the action is performed, and also the degree of proneness to act. The distinction between power, action, and activity of the mental faculties, is widely recognised by describers of human nature. Thus, Cowper says of the more violent affective faculties of man :-

" His passions, like the watery stores that sleep Beneath the smiling surface of the deep, Wait but the lashes of a wintry storm, To frown, and roar, and shake his feeble form.''-Hope.

And again :-

" In every heart

Are sown the sparks that kindle fiery war ; Occasion needs but fan them, and they blaze."

The Task, B, 5.

Dr Thomas Brown, in like manner, speaks of latent propensities-that is to say, powers not in action. " Vice already formed," says he, " is almost beyond our power ; it is only in the state of latent propensity that we can with much reason expect to overcome it by the moral motives which we are capable of presenting :'' and he alludes to the great extent of knowledge of human nature requisite to enable us " to distinguish this propensity before it has expanded itself, and even before it is known to the very mind in which it exists, and to tame those passions which are never to rage.1'1 " Nature," says Lord Bacon, - will be buried a

1 Lectures, vol. i. p. 60. See also Dr Blair's Sermon on the Character of Hasael ; Sermons, vol. ii.

POWER AND ACTIVITY. 167

great time, and yet revive upon the occasion or temptation ; like as it was with AEsop's damsel, turned from a cat to a woman, who sat very demurely at the board's end till a mouse ran before her." In short, it is plain that we may have the capability of feeling an emotion-as anger, fear, or pity,-and that yet this power may be inactive, insomuch that, at any particular time, these emotions may be totally absent from the mind ; and it is no less plain, that we may have the capability of seeing, tasting, calculating, reasoning, and composing music, without actually performing these operations.